Campaign History of the 151e Régiment d'Infanterie - XV

~ 1916 ~

Verdun - Third Tour - Part II (20-24 May)

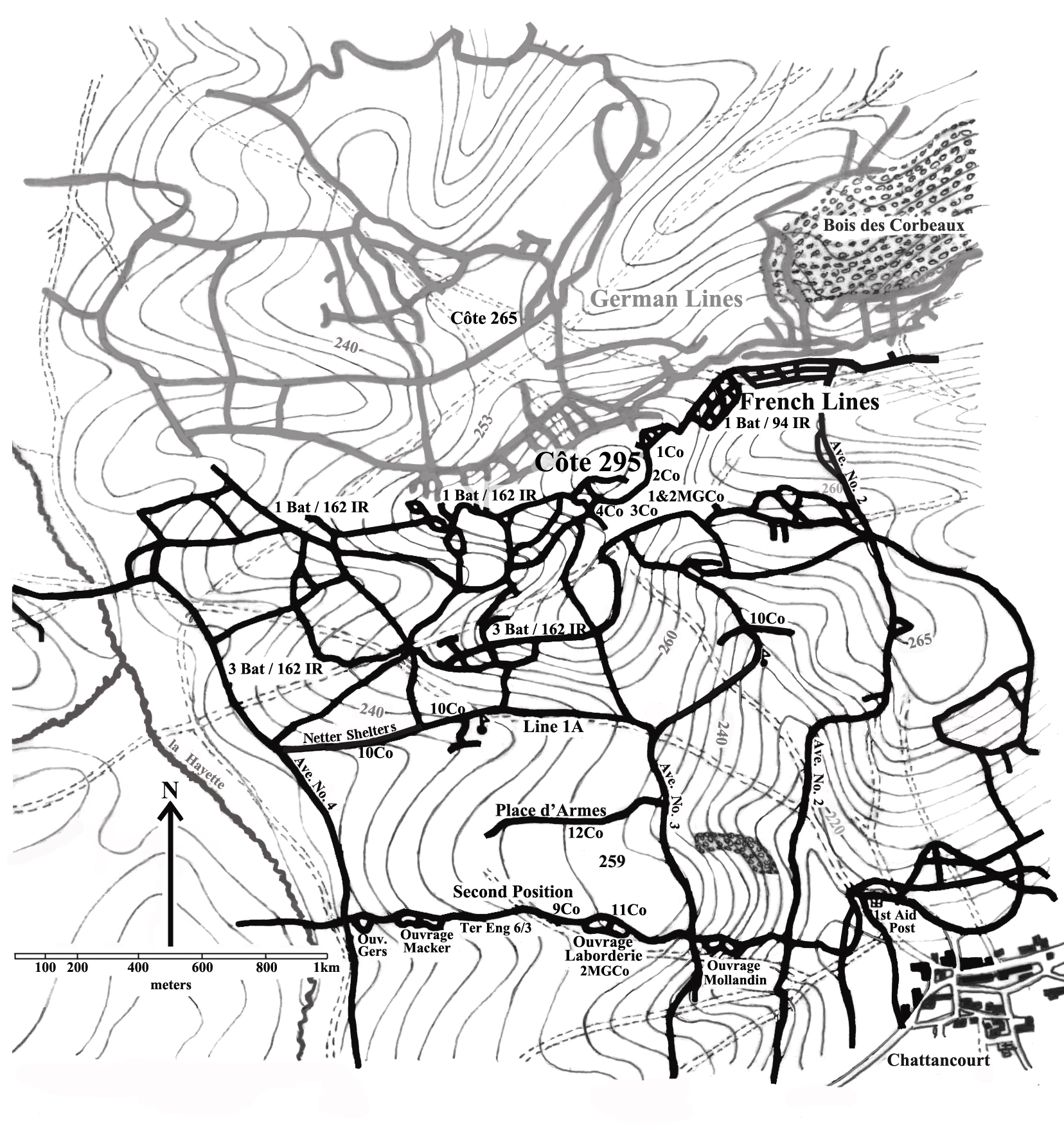

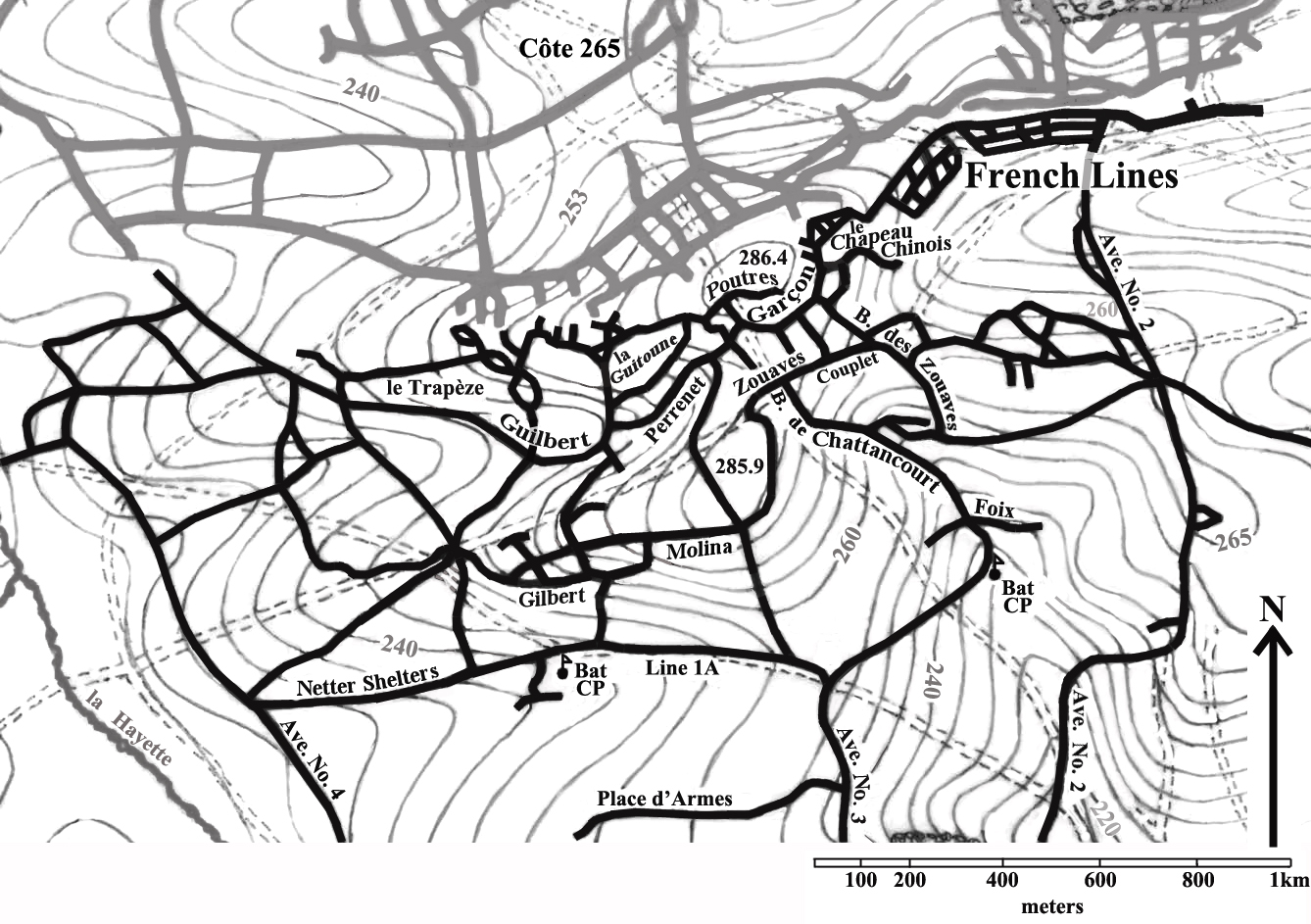

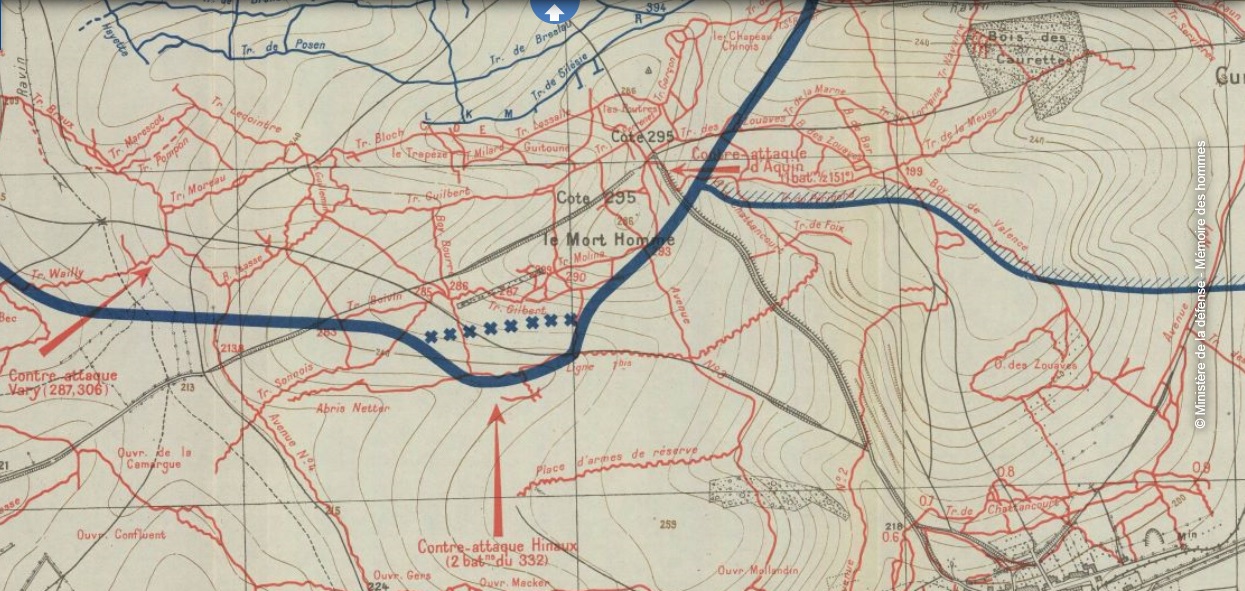

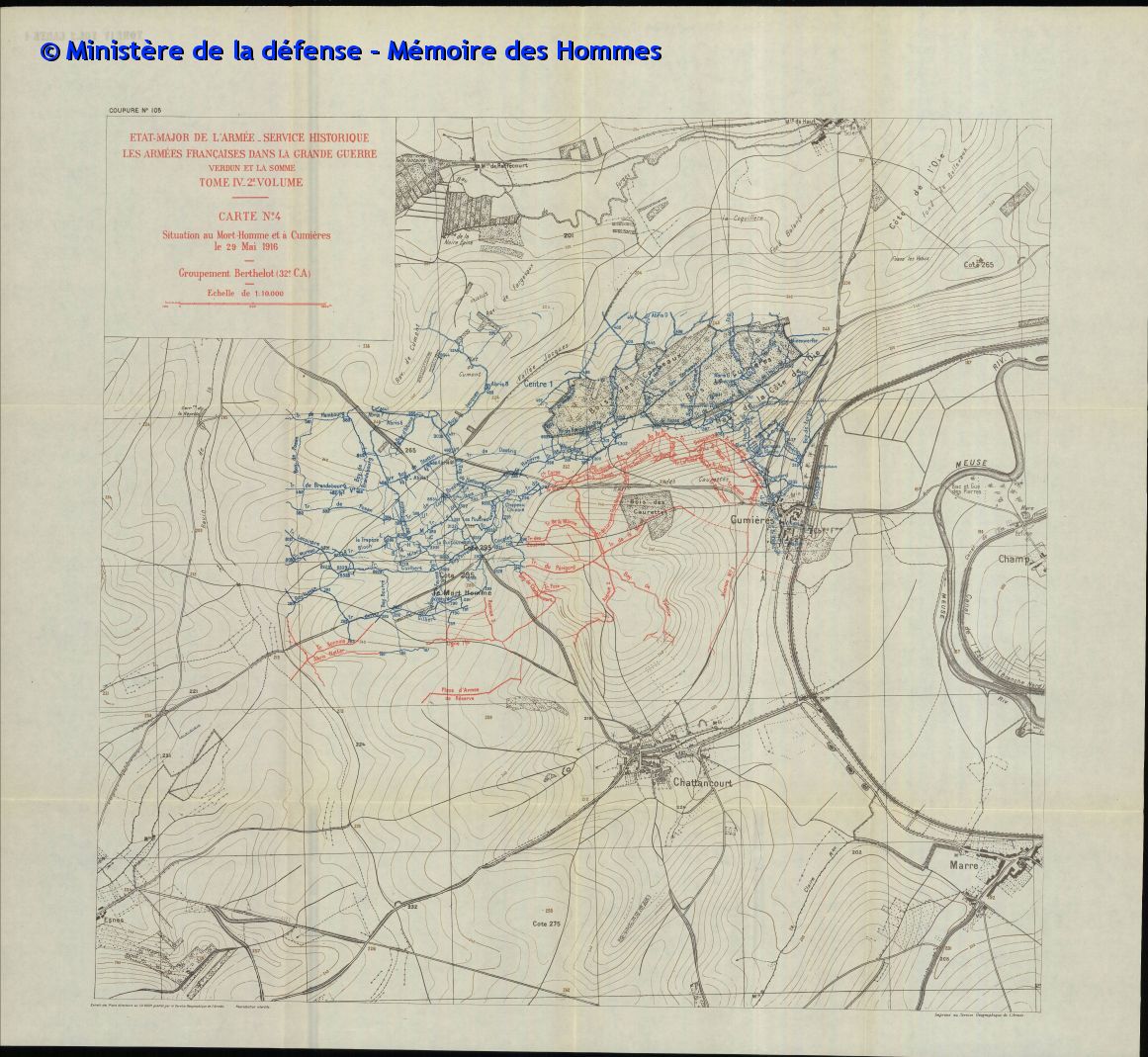

Left: map of Mort Homme showing the disposition of the 42e DI on the evening of 20 May 1916 (drawn by John Bracken). Right: map showing the entrenchments on the summit of Mort Homme.

20 May: the bombardment continues without cease now with even greater intensity throughout the entire sector with shells of all calibers, though primarily heavy shells (150s, 210s, and even 305s) and heavy minenwerfers (150s). Gas shells are also used, resulting in a great number of casualties. The heavy shelling completely destroys the first and second line trenches. The number of dead and wounded soar. The survivors now occupied a line consisted of nothing more than shell holes. Many rifles are buried or otherwise unserviceable. All telephone lines are cut, severing communications with regimental and divisional commands.

All intelligence now pointed to an imminent enemy infantry attack in the morning. Once the German artillery lengthened its fire, the assault waves would come. After eating his breakfast, Jubert left his shelter and find his section, now greatly reduced in size.

Fully equipped, revolver checked, helmet on, blurry and shifty eyed, with great difficulty, through the boyaux encumbered with sleeping men, I rejoin my section. Eight men with thick beards and clay-covered faces, whose calloused hands could easily cover over mine. Poor Jacques Bonhomme, the lot of them. Men of the earth and plow. In combat, it's only the peasant who fights.Jubert is informed an officer from the 267 RI (69 DI), acting as liaison with the 42 DI, is looking for him. Once they are presented to each other, the officer suggests they share the intelligence they have of the situation. Jubert responds that he's entirely ignorant of the situation and would be obliged to have any information his counterpart might have. The officer tells Jubert that he believes they are the target for a German infantry assault to be launched in a north, northwest direction via the Ravin de la Hayette towards the summit of Mort Homme.

Jubert then goes to take this information to Commandant Malochet and learns that the battalion has already been put on alert. Malochet orders that the 9 and 12 Cos. are to move across open country in front of their positions to height of the Colonel Marathel's PC. They will deploy to the west and thus form a defensive line in front of their current positions. The 11 Co. will remain with Malochet under his orders to act in the defense of Ouvrage Laborderie and its wings, in connection with the pioneers company and two machine-gun groups. Jubert is detached from his company to ensure the defense of the left wing. Jubert watches 9 Co. go over the top to the prescribed advanced positions. He can see that 12 Co. is already in place.

At 1400 hrs, a powerful German infantry assault is launched with the support of flame-throwers. Jubert describes the moment the attack begins.

Machine-guns set up, the men standing up with their heads above the parapet. Nerves are on edge in the seeming calm, we await the enemy. He does not delay. There's movement on the summit, a rush in a mist of dust and smoke. Through the binoculars, one can make out the gray uniforms. Arrayed behind the elements that are covering us and have opened fire, we wait to do the same.Despite heavy losses and local setbacks, the Germans manage to penetrate into Tranchée Garçon up to the liaison point of the two right companies. To the west, the Germans have broken through the front of the battalion of the 162 RI that was in first line. At 1530 hrs, German forces from the coming of two companies appeared on the crest of 285.9 coming from a northwest direction. These two companies rush down the south slope of 285 and head in the direction of the Ravin de Chattancourt. Commandant Oblet (commanding 1 Bat.) reassembles some men of his liaison around his PC and sets up a machine-gun that still remained available. This gun manages to surprise the advancing enemy infantry and stops it progress. The enemy force quickly withdraws back up the crest 285.9 where it installs itself, along with several machine-guns which takes the entire Ravin de Chattancourt by enfilade. Jubert account is similar to the official report:

The enemy hesitates, he disperses, he breaks. Then in another method, he retakes his advance. Now in singles, progressing from shell-hole to shell-hole. But our fire crackles away, the machine-guns adding in their voices. The gun barrels get hot in our hands. It makes us feverish. Right now we're the masters of death. The enemy stops, recoils, then gets down. Our gunfire searches him out and he pulls back now behind the summit. I can't help but admire him though in the minutes that follow when, under our unrelenting fire, I see him go out to retrieve the wounded.Two Taubes soon appear overhead and fire flares down on Jubert's position and suddenly a furious storm of shells comes crashing down around them. The trench is blasted wider, then gets flattened and reformed by the unending explosion of heavy rain shells. The men continue firing on the summit, as the air and ground tremble from the brutal force of the bombardment. News arrives that the Germans have progressed through the Ravin de la Hayette and taken Ouvrage Gers to their left. Their position was now in danger of being encircled by the enemy.

Jubert is told by one of his comrades that they will need to launch a counter-attack to retake Ouvrage Gers. With so few effectives left, Jubert goes in search of reinforcements to accompany him and his grenadiers. The JMO similarly mentions that the platoon of 10 Co. that had been in reserve has suffered heavily, with no more than 15 or so rifles still available, making the chances of it being able to counter-attack immediately all but impossible with them as well.

As he made his way along, Jubert comes across many dead, some singly, others in groups, all recently killed. He passed a machine-gun that's been destroyed with it's entire crew laying dead around it and forming the shape of a cross. When he encounters his friend, Sous-Lieut. Erkens, he's relieved to hear that the neighboring division had already retaken Gers, along with fifty German soldiers and two officers. Jubert returns to his shattered section to wait to be relieved. As much as he would like to get away as quickly as possible, orders arrive that Jubert is to ensure the liaison with the 69 DI and in turn, the 15 CA.

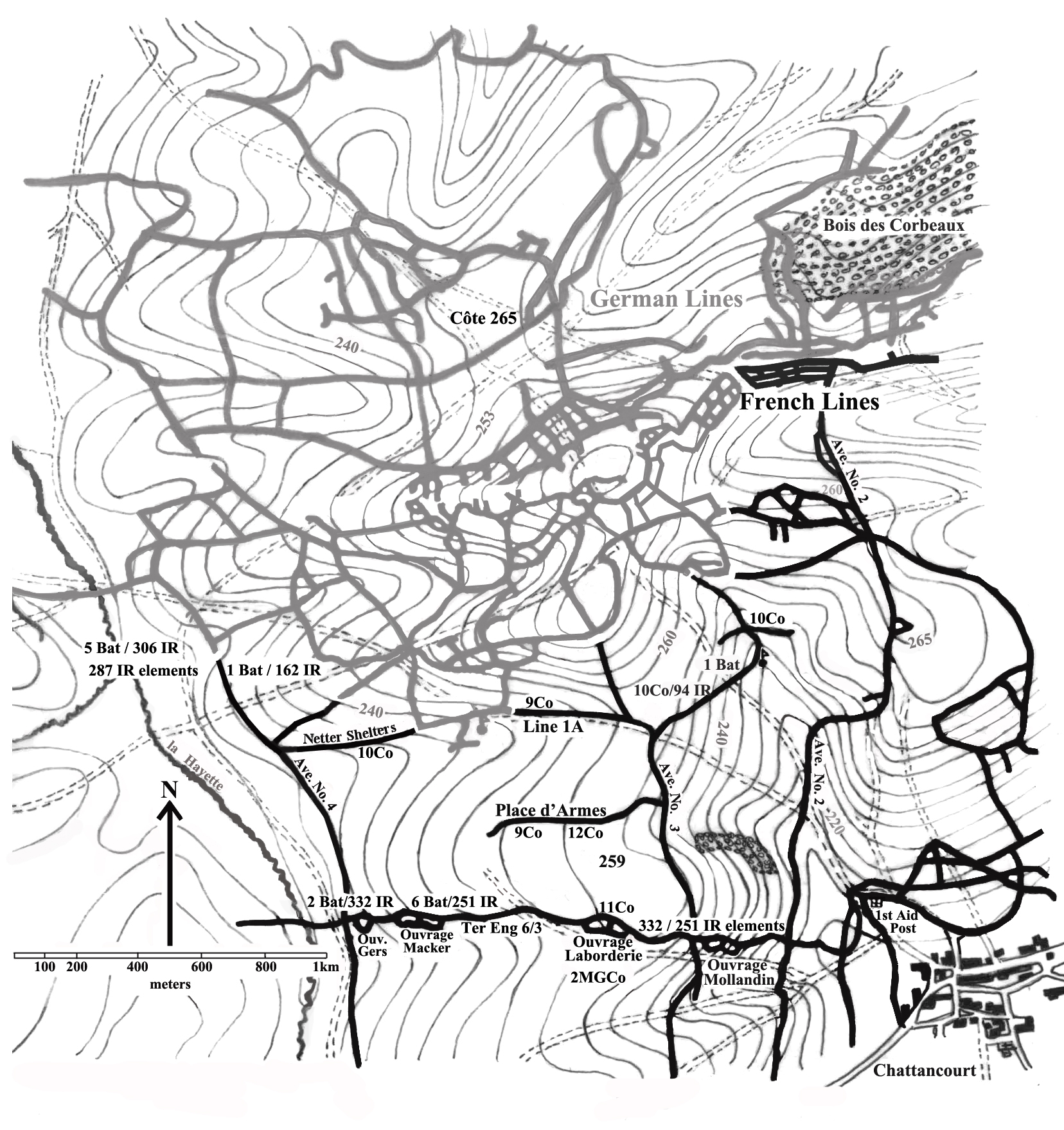

Left: the disposition of the 151 on the evening of 20 May 1916 (source: 42e DI archives) Center: Mort Homme sector in May 1916; labeled on the map are French counter-attacks of 22 May. Right: Mort Homme sector showing the gains made by German forces at the end of May 1916 (source: AFGG).

Links to maps are

here and

here.

At night, reconnaissance is carried out to ascertain the points occupied by the enemy. They are found to be occupying Côte 285.9 and established to the south of Tranchée Couplet up to the intersection of this trench with the Boyaux de Chattancourt and Zouaves. To the west, the Germans have made it into the French lines via the Ravin de la Hayette and are threatening the second position.

The 9 Co. receives orders to extend itself to the left in the place d'armes, where the 12 Co. is in place. This ensures the liaison with the 287 RI. The 11 Co. provides security for the second position with the Engineers Co. 6/3 ter. The night passes without another enemy attack. The survivors of 1 Bat. (around 50 in total) are reformed by Commandant Oblet, who defensively organizes the positions still in friendly hands.

At the bottom of a light shelter, sitting cross-legged with his head resting on his chest and surrounded by his men, Jubert listened for the slightest sound. As elements of the 69 DI, Jubert overhears “By regiment, a battalion will engage; we attack around midnight.”

Commandant de la Ruelle arrives from the 64 RI and takes command of 2 Bat. Initial losses for the regiment on 20 May include 48 killed, 169 wounded, and 462 missing (for a total of 679).

21 May: During the day the situation remains the same and the German bombardment continues with the same level of intensity. A handful of men manage to hold onto a portion of Tranchée Couplet, clinging onto the ground. But around them to the north, east and west they cannot hold on under the shower of German grenades. Having lost all their NCOs, they are forced to pull back to Tranchée Foix, which now constitutes the new first line trench. After the arrival of reinforcements at the second position, the disposition of units is as follows from left to right: 12 Co., two companies of the 251 RI, 9 Co., Engineers Co. 6/3 ter., 11 Co. All these units have suffered heavy losses from the bombardment.

Late in the morning, the 2 Bat., which was at rest at Jouy-en-Argonne, are alerted and report to Fromeréville. It was around noon on 21 May*, under a broiling sun, Bordinat with the rest of 2 Bat. began the long hazardous journey up to Mort Homme. As much as possible, the battalion moved under cover of a tree line, where the first heavy shells came down intermittently. Proceeding in single-file, they would arrive at Froméréville in the early evening, already drained from the march. There they stop here to have their soup and refill their canteens with water (they'd already been warned how rare a commodity it was at the front).

Note: the dates recorded by Bordinat in his account do not align precisely with the events as recorded in the regimental JMO of the 151. At the same time, there are discrepancies in the JMO of the 151 in the period of time covered. For example, the JMO of the 151 states that the entire regiment was at rest by 23 May following its relief by the 254 RI. However, Bordinat’s account however states that the remains of his company (6 Co./2 Bat.) was belatedly relieved by the 150 RI early in the morning hours of 24 May. Bordinat’s date is backed up by the JMOs of the 150 RI notes that two of its battalions would relieve elements of the 151 RI (along with the 332 RI) on the night of 23-24 May, with the relief not being completed until 0100 hrs on the morning of 24 May.

As darkness falls, a light fog settles in and at 2100 hrs, the 2 Bat. sets back off again to complete the final leg of the journey up to the front lines at Mort Homme. As they move up the line, they pass heavy artillery batteries to the right and left, which were firing away without stop. At each discharge, a large red flame leaps out and shakes the ground. All around them and hidden in the wooded ravines, the guns thunder away.The further we march, the more frequent the noises grew and you couldn't help from receiving a shudder by the unexpected departure of the repeated shots around us. We took it all in humble silence, these guns that brought death far away with every passing minute.Around 2200 hrs, they are given a brief rest. Under their heavy loads, the men are already exhausted from the march and quickly stretch out on the ground.

And, God, what silence, no one talks, no one complains. What are people thinking, no one can say. Good things alas, and me (as a novice), I look with an anxious eyes at the flares. The sky is all lit up. All of these things are new to me. It reminds me of my country's July 14th festivities. At the moment, one of our dirigibles is assisting with the bombardment, which comes is doubtlessly coming back from a trek amongst the enemy. What a contrast! Everywhere in the air, on the ground, in the distance, there is only fire. On our left, the burning fires in a neighboring area also help to illuminate these sad plains. What a sorry sight!Heavy shells fall around them as they take to an interminably long boyau. Bordinat is completely dumbfounded. He doesn't know what to make of it all. All he knows is that they have to arrive before daylight, or else risk being spotted by the enemy. The shells come down around them and men are hit by shell-fragments.

Moving in single-file at the double, from time-to-time, we call back to each other to make sure the man behind is still there. The response is given without the man ahead turning around to see, for there are already many men who've been killed or wounded. We move up without caring so that we don't lose the column and the show becomes more and more frightening. Many do not arrive, the boyau has already been filled with corpses for some time. We keep moving up, we fall down and we pick ourselves back up again.As Bordinat and the men of 2 Bat. had been laboring their way up to the front, Jubert (3 Bat.) had spent a miserable night biding time as he was responsible for ensuring the liaison with relieving units. While the bombardment in the sector had stopped by this time the night took on frightful aspect as the low rolling clouds were illuminated yellow by scores of flares. A small reinforcement of eight young recruits from the class of ’16 arrives with Jubert's section later in the night. The German artillery becomes active again around the same time. Jubert’s section is soon joined by a company of 332 RI. Like many companies of the 151, it was severely understrength, with only 30 effectives remaining. Jubert gets his men ready to move out just as a shell comes crashing down close by, throwing three men to the ground. One is killed outright and another, bleeding from his buttocks, runs away screaming. The blast also knocked down Jubert. Recovering from the shock, Jubert organizes his men and they start making their way back to the rear. His men have a stupefied look and are quiet. But he can see the hope of making it out of there alive has given them hope and sparked some life in their eyes.Despite our physical fatigue, our nerves carry us forward like the breath of the poor, no longer feeling the heavy packs and despite our concern, at the least stop, we swallow a mouthful of water from our canteens already nearly empty. Now we smell a pungent, nauseating, overpowering stench.

We collide and bump into men of other relieving units lining the trenches for more than a kilometer, stepping over hundreds of corpses. It’s a trial of slaughter, yesterday my section was targeted to the full extent. What does it matter to me? It just shows me more horror.While waiting for further orders to pull off the line, Jubert falls asleep alongside his men in the trench for an hour or two.

“And if you saw the Place d'Armes, lieutenant! The 2nd Battalion found its grave there.

“Any news of the business from yesterday? “The 1st Battalion is gone; we only know that Commandant Oblet is not the hands of the Germans, but no one knows where to look for him without coming across the enemy.”

“No survivors?

“A few loners, their minds so gone they no longer say a word. Captain Ritter, wounded, missing. Captain Boissin, Lieutenants Caslelbaron and Jubien are missing; Captain Detrais crushed. But let me stop there, lieutenant. Have your men eat their cans of reserve food. There won’t be any resupply tonight.

When I wake back in up, dawn is spreading. "How about the relief?"Jubert and 12 Company had not been forgotten though. It was the 2 Battalion that was their relief, and as can be seen, the approach up to the front was filled with endless difficulties, delays and dangers. It was just before dawn, that Bordinat and 6 Company would at last reach the battered second-line, where they encountered a large crowd of men from the 332 RI, 251 RI, along with elements of the 3 Battalion of the 151 RI. The 6 Company did not stop here but quickly pressed on through this mass of humanity, knocking into the dazed men who are passed complaining. All these wearied men wished to know was whether it was their turn to be relieved and if they had any water they could spare. With pangs of guilt and without stopping they responded they didn't. Meanwhile, Jubert had the men of his company assemble for the descent back down Mort Homme.

"We're still waiting, lieutenant.

"Get on your feet quick! Inquire around. Go to the commandant's PC, to the lieutenant's shelter. Maybe they've forgotten us?

"There's no one with us anymore," the man says upon returning. "At the commadant's PC, an officer of another regiment threw me out. I asked this lieutenant about the 151st, he told me: 'It's on the ground'. I lit my lamp; I saw a heap of men. I thought they were asleep, so I shook several of them. There was nothing to do; they were all dead."

"Clearly we've been forgotten," I say aloud. "Assemble the section."

After catching their breath, they start back off, passing the Bois-Bourrus, then Sivry-la-Perche, where the men remark on the presence of grass growing. Finally arriving at Jouy-en-Argonne, they are greeted by friends. When Jubert is told of the deaths of his friends and fellow officers, he responds simply:My men formed up, I point out that it's dawn:

"In half an hour, the bombardment [will begin]. It's useless to waste time going through the obstructed trenches; We'd be quickly pounded. A bit of courage; jump up on the parapet. The balls can miss us. In a little while, the shells will not. "Let's go, lieutenant."Through the shell-holes, running, stumbling, tumbling into craters, we cross the vast plain. One machine gun spots us but doesn't deem us to be a good target. Only a few bullets whistle past us. It was a great surprise to us, so we're happy fellows. Even six kilometers away from Mort-Homme, reliefs are not made until night. Crowded by ghosts, it seemed that the field of the dead would only let the shadows escape by mistake.

"We can't go any further, lieutenant.

"In step, boys," I tell them. "One hundred meters more, then we rest behind the ridge." A few minutes later, behind a battery whose gunners are washing up at the moment, we hold up sheltered in a little wood. "Rest for as long as you you want. How many are we?"

"Nine. "That's it? And the reinforcement? "Reinforcement included. Of the eight men who arrived yesterday," a corporal says to me, "only two are left."

"War is sad. Give me some pinard." Following my example, the men drink. Wine in profusion. This is the last blessing of the dead as their rations added to the welfare of the living.Losses for the regiment on 21 May include 15 killed, 37 wounded, and 60 missing.

22 May: As Jubert and the battered companies of 3 Bat. were struggling back to the rear, the 2 Bat. finally arrive in their assigned positions at dawn. Bordinat with the 6 Company were in the second-line midway up the slopes of Côte 295. The 7 Co. positions its sections along the Ravin de Chattancourt, establishing the liaison between Tranchée Foix and the units to the left in the 120 mm gun shelters.

Under the continual fire of German heavy artillery, the trench had already been reduced in height to five feet. Troops from multiple regiments (at the time, elements of the 251, 287, 332, and 162 RIs were all occupying this sector) were crammed into narrow trenches. Literally packed in elbow to elbow, it was necessary to climb over other men in order to let stretcher-bearers and liaison agents to pass. All the while, clouds of dust and smoke filled the air as showers of broken stones came raining down from above like hail, bouncing off their helmets with a sharp rap.

As the sun rose, the day got hot and together with the acrid smokey, dust filled environment, further exacerbating the growing sense of thirst. By noon, the heat and stench of rotting flesh had completely overwhelmed them. To help relieve their parched lips, a small bottle of mint liqueur was passed around. But by the end of the day even this was gone. Bordinat and his comrades could only wait for the nightfall in the hope that a search could then be made for water. To the contrary though the fire only doubled in intensity, principally on the place d'armes and the second position, and reaches (as the 332 JOM records) "proportions heretofore unknown." Bordinat recorded:

It is a deafening din of howling [miaulement]. In this dry weather, smoke mixed with dust to form a dark cloud that seized our throats, making a bitter taste that made us thirsty, though there was nothing to drink. If only we still had water! And this feeling got increasingly worse.Another man in 6 Company underground the same hell was the telephonist and radio telegrapher, Sdt. Pierre Rouquet. In an interview many years after the war, Rouquet recounted the grim conditions faced while fighting on Mort Homme. The one feature that dominated his memory was the brutal, unceasing shelling by German guns. Their positions had been so deluged with fire that the trenches had disappeared and the line consisted of nothing but shell-holes. Rouquet saw many of his comrades blown to pieces or else buried alive by shell bursts, and this was the fate he would nearly suffer. He recounted:By noon, we are wiped out by the sun and the smell of rotting corpses around us. But what can we do? The suffering doubles the feeling of thirst. What terrible sickness. What we wouldn't give for a little water.

You couldn't describe the deluge of fire that swept down on us. I was conscious of the danger of being killed every second. I had the luck to come through those first fifteen days. But I ended up stupefied. I felt as though my brain was jumping around in my skull because of the guns. I was completely dazed by the severity of the noise. At the end of fifteen days we came back down, seven to eight kilometers from the front to Jouy-sous-Lomballe [Jouy-en-Argonne]. And that we thought was the end of our spell at Verdun as far as we were concerned. We had one quiet night’s sleep, just one, that’s all, then the next day the battalion that had relieved us was wiped out. They had lost as many killed as were taken prisoner. There were five or six left out of a whole battalion. No more.At this stage of the fighting, German troops occupy 300 meters of terrain along the line 1 bis (or, line 1A). The 151 JMO records the exact position as Côte 285.9). Their presence creates a gap between the right subsector and the Netter shelters. In order to close this gap, elements of the 287 and the 306, the 332 and 151 RI are ordered to advance from the west, south and east respectively, and thereby encircle the German forces on Côte 295. One company of the 151 attacks and takes 100 meters of trenches between line 1 bis and the Boyau de Chattancourt, and occupying the latter. The liaison was reestablished with the 332 RI, with a machine-gun section placed in the Boyau de Chattancourt near the PC of the battalion commander and another placed at the end of the place d’armes. These inflict seriously losses on the enemy and effectively shut down all enemy movement in the Ravin de Chattancourt. On the left, the attacking companies of the 332 RI are able to make some progress but are unable to link up with the 287 RI and must entrench in place.We were sent up again in all haste to face another bombardment, one worse than ever. 210 [mm] shells were come coming over four at a time and we were being buried with every volley. Men were being completely entombed. Others dug them out. This lasted all day during the preparations for a German attack. My moment came on the stroke of 7 o'clock. It was my turn to be buried, and you must understand that I suffered greatly because I was unable to move. I could do absolutely nothing. I remember saying to myself, "Well, that’s it at last!" and I lost consciousness. I was dead...And then I was being disinterred with picks and shovels and they pulled me out. [I was] totally exhausted. My captain [Captain Olivier] said, "Lie down over there." Later he sent me to a first-aid post two kilometers back.

Night fell and I could see the red flashes of shells passing in front of me. At the first-aid post there was a major engaged in looking after a German whose leg had been badly smashed. The major put a dressing on him, and the German begged him, "Finish me off!" The major told me, "I don’t have the time to see to you. Go over there." I went over to where he pointed. I hadn't been there five minutes when a shell landed on the major and the German. That’s destiny. You’re marked by fate. [On est marquée.] After that we were sent down to the field kitchens. I was evacuated. I gather I stayed four days in a corner, exhausted, in total shock.

Meanwhile, hours pass under the same relentless shelling as night falls. In the early morning hours of 23 May, the fire slackened somewhat. Still tortured by their thirst, a few of Bordinat’s comrades who knew the ground offered to go out to look for water. He handed them his canteen and they set off. A long time past with no further word. Sadly, the men were never seen again and more bodies decorated the savage slops of Mort Homme.

During the night of 22-23, the elements of 1 Bat. are relieved by elements of the 254 RI. Losses for the regiment on 22 May include 22 killed, 22 wounded, and 6 missing.

23 May: While, the 1 and 3 Bats. were bivouacked in the Bois des Clairs Chênes and recovering from their time at Mort Homme. The 2 Bat. remains in the place d'armes and second line position. As night slowly turned to day, a pale morning light filtered weakly through the smoke and dust that enveloped the ridge. The temperature begins to climb again. Dry mouths, cracked lips, scratchy throats, heat, thundering, smoke and fire.

The infernal machine continues. We’re surveilled by enemy planes which regulate the fire of the guns. Now the shells get closer to our trench, big 210s. One of my comrades tells me we’ve been spotted.Desperate to relieve the thirst, Bordinat and a young soldier from the class of ’16, collect up the abandoned canteens that lie scattered about. Setting off at a run across the desolate plain in order to cover the 1500 meters back to Chattancourt. Knowing it was forbidden to cross out in the open, the boyaux had been so leveled that sticking to them was a moot point. Bullets whistled by indicating that the enemy on the ridge above had likely spotted them. But their lust for water drove them forward despite the prospect of death. Along the way they have to step over the countless bodies of French and German soldiers killed in the German attack of 20 May.Indeed, it ‘s destruction, carnage. Many are swallowed up, pulverized, decapitated. Our trench is half filled in. Those who aren’t wounded, like me, remain impassive, stoic, awaiting our own death. We endure the terrible shock of the explosions, often only a meter or two from us and a few moments later one land a meter and a half from me and my fighting buddy, Boisson. But miraculously it does not explode, although it still caves our trench in.

Now all the survivors are basically exposed without any cover. Finally the enemy calls off its big guns at 8 am. Only 77s continue to burst, but this is a mere toy to us, which we pay no mind. Tools, shovels and picks are brought to us. Where do they come from? We have no idea. We scoop away this disastrous mess to try to uncover, if possible, those comrades who’ve been buried alive. But that accursed thirst that brought so much suffering has still not left us.

After making it some distance further, Bordinat and his companion come across others who had gone in search of water and knew where to find it. At last, they are led to a small muddy brook that ran through Chattancourt. Getting down on all fours and lying flat on their stomachs, they guzzle down the dirty water in large gulps. After satisfying themselves, they fill up the canteens of their comrades with their cups and head back up to their positions with their small gifts. The men would not have much time to relish in the temporary relief the water brings them. Soon salvos of 210 shells begin thundering back down again, the devastating blows further collapsing the trenches.

The awful business starts up again, the living burial continues. Armed with shovels and picks again, those still standing set back to the task of saving those still alive by clearing away the earth and stones from the victims. At last we manage to pull out a few survivors, the others having been asphyxiated after ten minutes. In turn the captain’s CP is caved in with his entourage, the lieutenants and some men all suffocating in their airless hole. We start to dig it out and after some time, we can hear the cries and groans, which gives us a little more hope and eventually, we get them out. The captain and lieutenants are unharmed and our commander tells us to keep digging as several more are at the bottom. We keep on picking for a little while but our strength leaves us and we’re unable to continue. All of us are exhausted and give up. Of the twenty survivors, not a single one is capable of exerting more energy. What can be done? And so, despite our best efforts, the bodies of our buried comrades remain under the soil of this cursed ridge.Those still clinging on in the trenches are silent. Their minds think of everything and nothing. They had been transformed into living statues, their skin taking on a yellow waxy look. The trenches are reduced to nothing more than shallow ditches. With no other form of protection, some men pathetically shelter under their packs to protect against the razor sharp chunks of steel that slice through the air. The constant landslides and showers of earth caused everything to buried: equipment, rifles, men. Occasionally stretcher-bearers carry away a sad wreck of a human being, filthy, crumpled, and bleeding. And despite the unfortunate fate of the injured man, those who remain cast an envious eye to those who've seemingly escaped the furnace.The same infernal bombardment goes on. You could say it was like a tremendous reaper sweeping back and forth from right to left and razing everything. We are completely demoralized and unable to move, we’re dazed by this rolling thunder. Eventually we are lulled to sleep by the noise, until the moment that an explosion goes off very close by and wakes us back up from our reverie. The jolt pulls you out of your stupor a bit, gives you a shudder, and then five minutes later you doze right back off. How long these frightful days were, waiting for death while we nodded off. And when sleep abandoned us, from the other end this damned thirst gnawed at us and had to be endured all the same. We could eat but who would want to put anything in their dry throats, burned by the alcohol that we had previously drank. And the stench we couldn’t get out of our noses, these proved to be the real enemy. It wasn’t the Boche. On the contrary, how happy we would be if only we could see this detested race of people coming at us on days like that.

We remained there, laid low by our thirst, under this storm of steel and fire passing over our heads. On the ground soaked in blood, what horrible existence and horrendous sights are seen. How do you ever get these terrible things out of your head? It didn’t matter where we were, we could never forget this terrible life that had been engraved in our minds.

Suddenly at 1900 hrs* the shelling rapidly subsided and for a few moments, an deafening silence fell over the smoking churned up land.

"Get up!" our captain shouted. "Fix bayonets and everybody get up of the parapets, the Boches are coming!" The sharp cry resounded in this moment of calm and had the effect on us like a spring. Rifle in hand, all ready and loaded, with a bound we climb up and wonder where are these human wrecks of come from. No matter, everyone is determined to make the enemy pay dearly these nameless sufferings we’ve had to endure since our arrival.A sense of satisfaction could be keenly felt amongst Bordinat and his comrades as they dropped back down into their holes. But as they did, the German artillery opened back up, their angry fire focusing on the French gunners behind the French first-lines. What’s worse, the maddening thirst once again seized at their parched mouths and burning throats. The same malaise and dispiritedness began to return but as it did, miraculous word arrived that they would be relieved later that night by elements of the 150 RI. This gave them the strength to hang on a little while longer -- an end was at last in sight!Red flares go up all along our line. It’s to signal our 75mm guns, which now come alive as well and in their turn, play the dance the Boches know well. And this change in noise, mixed with the crackling of our remaining machine-guns, we move us to let out bravos after our long silence. The enemy wave is then decimated, doubtless leaving only desolation and the dead. When will it be our turn?

The thunder was in full swing. Arms and legs fly through the air and in five minutes, everything is swept away. Five or six make it to us, unarmed, running with their arms up in the air crying out "Kamerades, kamerades." Each of them was wounded one way or another, and as much as us, were pale and looked exhausted.”

* The JMO of the 332 RI confirms the time and date of this attack as 1900 hrs on 23 May.

Indeed, as the JMO of the 332 RI recorded, a strong German infantry attack is launched on the French (former) second line positions, between Boyau 3 (Avenue 3) and Boyau Bourre along the entire front. On the right, the enemy force that rushed down the southern slope was battalion-strength in dense formation. The force is mowed down the combined rifle and machine-gun fire of elements of the 332 RI. On the left, another battalion-sized enemy force attacked from north to south down Tranchée Gilbert, and from west to east upon exiting a blockhouse. This second group attacked using flame-throwers. After initially pushing back the French defenders, a counter-attack was launched, repulsing the German advance. This force was then too cut to pieces by French machine-gun fire.The torturous hours dragged on. By midnight, their relief had still not arrived and the men wondered anxiously if they were still coming. Finally, around 0130 or 0200 hrs, they see the silent arrival of the 150th*. Meekly, they ask if their replacements for a drop of water and each of them is permitted a swig from a canteen. Dazed, aching and feverish, the survivors of Bordinat’s company must now make it back to the rear with only a few hours till before daylight would betray them to the enemy. Conscious of the terrible condition of their men, the officers simply prescribed an assembly point, the Bois Bourrus, for the men to meet back up. Each man was to make their own way back as best he could. And so in small groups, the men begin the descent back down Mort Homme and across the wasteland toward the rear. Occasional salvoes of German shells obliged them to thrown themselves flat on the ground until the storm of shell-fragments and shower of earth and stones passed. Then with considerable effort, they would silently pick themselves back up and continue to slowly trudge away from the zone of danger and death.

* According to the JMOs of the 332 and 150 RI, the remnants of 2 Bat. would finally be relieved by elements of the 150 RI late in the night of 23-24 May.

After a few hours, Bordinat and his friends reached the Bois Bourrus at dawn (24 May), half-dead yet somehow still standing. Spotting La Claire spring, they got down on all fours and gulped down the cool, gently flowing water. After splashing some water on their faces, they filled their canteens up and then reassembled to continue the march to the Bois des Clairs-Chènes (south of Jouy-en-Argonne) where they would board trucks that would take them to Brillon for rest and reorganization.

At 2100 hrs, the 1 and 3 Bats. board a train at the Baleycourt station and will be taken overnight to Robert-Espagne. Sous-Lieut. Cartier arrives from the 34 RI and is assigned to 2 MG Co. Sergent Daudrimont receives the Medaille Militaire. Losses for the regiment on 23 May include 23 killed, 37 wounded, and 13 missing.

24 May: The 1 and 3 Bats. (along with the regimental staff, CHR, and 1 and 3 MG Cos.) disembark from the train at Robert-Espagne and march to their billets at Saudrupt. Meanwhile, after marching throughout the night and the next morning (24 May) to the rear, the 2 Bat. boards trucks (probably from Baleycourt) and are driven to Brillon for billeting, along with 2 MG Co. and Engineers Co. 6/3 ter. Losses for the regiment on 24 May include 3 wounded and 6 missing.

Once again, the 151e RI (along with the other units of the 42 DI and 69 DI) had been severely tested at Mort Homme. The 20 May in particular has been another day of horror for the 151, on parallel with other darks days in the regiment's history. Many companies had suffered over 80% casualties. The 2 and 3 Battalions were especially hit hard and suffered catastrophic losses. Preliminary reports put the number of casualties for the regiment on this one day alone at around 680 killed, wounded, or missing. The number of those missing (462) is particularly striking and, likely, more accurately reflects the number those left dead on the field (including many who'd been buried alive or torn to pieces by the heavy artillery fire). These losses are magnified by the additional casualties suffered in the days before and after 20 May. During the twenty days the regiment spent on Mort Homme in May, it had suffered 1100 casualties -- almost half of its entire effective and the greatest loss in men since the dark days in the Argonne in the summer of 1915. The other units of the 42 DI also suffered heavily. For reference, the Divisional Stretcher-Bearers Group of the 42 DI processed, between 5-23 May, 534 dead, 2,364 wounded, 433 sick cases (total of 3,331) and this includes only those who could be evacuated.

The 151 had served three tours in three months at Verdun. It had been a severe series of trials, with the regiment suffering roughly 1,800 killed, wounded, or missing. The May tour would be the last it would undergo during the Battle of Verdun proper. However, it would be sent back to Verdun the following year for the French army offensives that would be launched there in July and August of '17. But for now, the regiment would be given a period of rest, refit and retraining before being called on to take its part in the Battle of the Somme in the fall of '16.