Campaign History of the 151e Régiment d'Infanterie - XIV

~ 1916 ~

Verdun - Third Tour - Part I - (5-19 May)

5 May: The regiment will return to Mort Homme. The 1 and 2 Bats., along with the regimental staff, embark Brillon in trucks at 0700 hrs and are taken back to Blercourt. There they will pass the day in the Bois des Clairs Chênes (northwest of Blercourt). The 3 Bat., together with Engineers Co. 6/3 ter. and the CHR, are transported by rail and embark at Baudouviliers at 1400 hrs and get off at Baleycourt, along la Voie Sacrée, where they then rejoin the rest of the regiment at the Bois des Clairs Chênes.

After the evening soup, 1 and 2 Bats. go up to Mort Homme to occupy positions in the right subsector. The 2 Bat. takes up the first line on Côte 295 with three companies in line (from left to right: 5, 7, 8) and one in support (6). The 1 Bat. takes up the second line with two companies in the place d'armes (northwest of Chattancourt) and two companies in the second position (the line of ouvrages a few hundred meters to the south). Moisson and his staff, along with the CHR, Engineers Co. 6/3 ter. and the 3 Bat. are bivouacked on the hill north of Jouy-en-Argonne (10 km southwest of Mort Homme). German artillery heavily bombards the sector, though fortunately no men are lost.

Sous-Lieut. Campana is back at the front. Not long after his arrival, he is wounded in the chest by a grenade fragment. The wound is not serious as the fragment fails to penetrate, but it does cause significant bruising to the skin and makes his breathing a little difficult. In his usual way, Campana declined to be evacuated from the front. In actuality, he had underestimated the severity of the injury. The grenade fragment had lodged itself into the top of his lung and he would soon be coughing up blood. But it was the events that would unfold a few days later that would prove far more dramatic.

From 2100 to 0300 hrs, his section had to continuously transport logs, spools of barbed-wire, crates of grenades, and bags of cartridges. On two occasions Campana nearly fainted from the excruciating chest from the grenade fragment wound and ongoing stomach pain he suffered. Nonetheless, he saw the job done before crashing in his shelter. The pain did not subsided and he began coughing up blood. Nonetheless, Campana refused to abandon his section, instead requesting that a vile of opium be brought to him.

Lieut. Caheu transfers to the Instruction Center of 3e Armée.

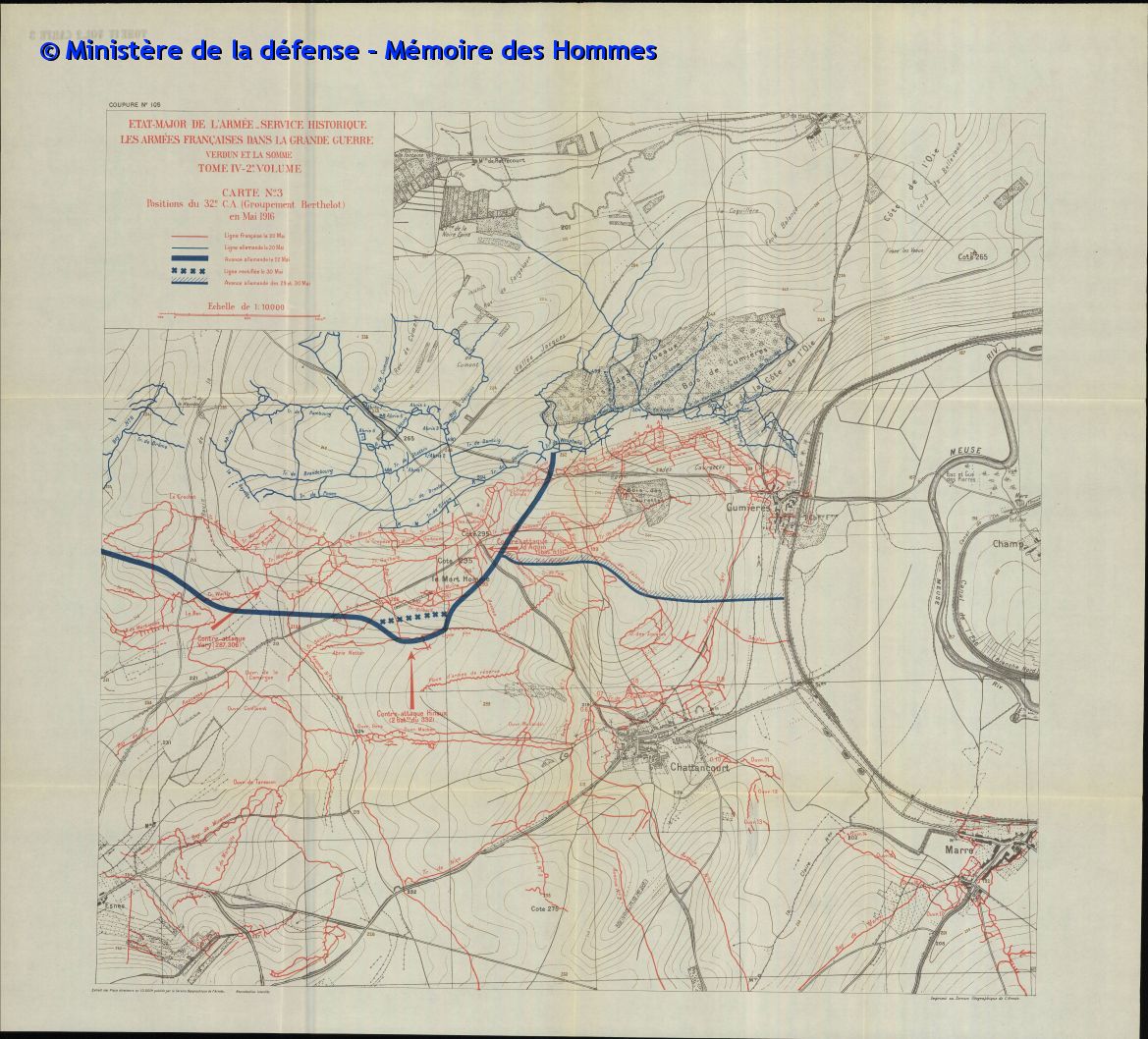

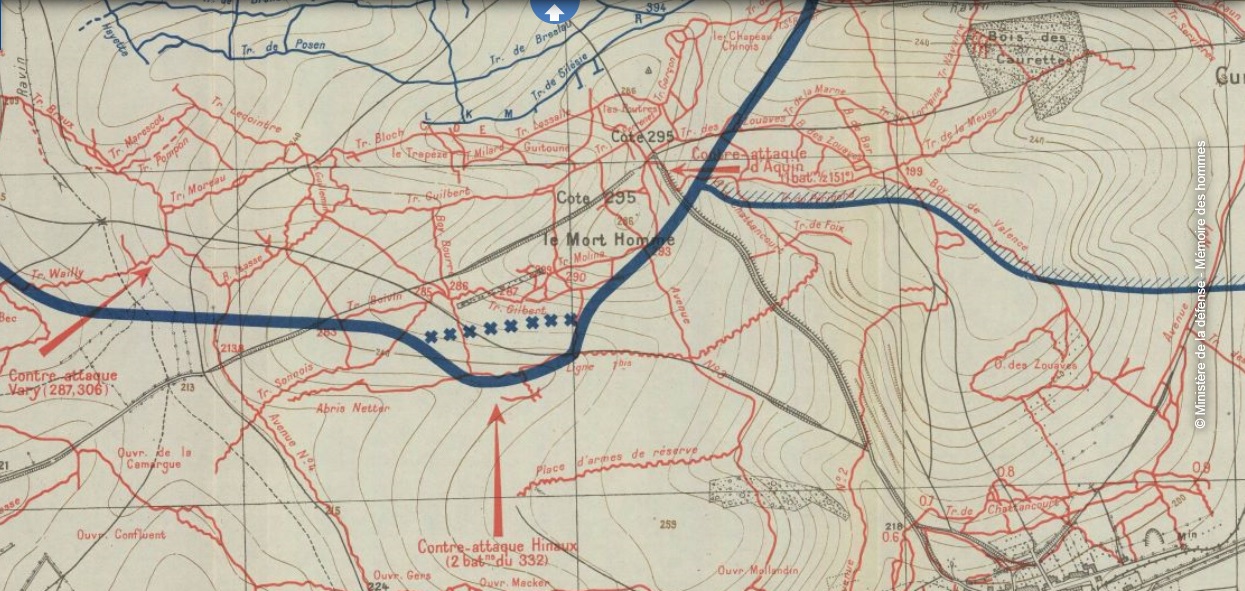

Le Mort Homme sector in May 1916 (source: AFGG). Labeled on the map are French counter-attacks of 22 May. Link to map is here.

6 May: The regiment occupies the same positions and works to deepen the existing trenches and boyaux. In concise terms, the JMO simply notes that the German artillery remains highly active. What was it like to be under the shells though at the time. Campana provides a vivid description of what it was like being in heavy shelling at Mort Homme. At noon, Campana noted that the bombardment had intensified, with shells not only following around his trench but in it. With the help of one of his men (for he could barely stand on his own), Campana emerged from his shelter just as a 210 shell landed in the near boyau, shattering rifles, collapsing the parapets, and killing and wounding a dozen men. One of the victims was hit by a shell fragment as big as a bottle, which disemboweled him a few meters from Campana. The man collapsed to the ground wailing in agony. Rushing up to the wounded man, he could see that his abdomen was open from navel to pelvis, his intestines spilled upon the ground around him.

“Oh, lieutenant, don’t let me suffer like this, it’s unbearable. Put a bullet from your revolver in my head. I can’t stand it any longer. You know I’m fucked, so why let me suffer needlessly. Or if you’re afraid to, give me your weapons and I’ll do it myself!”Incredibly, though the man suffered terribly, he was still alive some hours later, his pain lessened from morphine. While his ultimate fate is not known, the man would survive at least a couple days longer, thus sparing Campana from any guilt at killing one of his own men. Campana’s reflections wouldn’t last long as another 210 struck down close by, this time killing the corporal standing beside. Campana had his body brought into his shelter and just as he did, a 105 exploded close by. He rushed out to see his orderly hurriedly digging away some earth, despite the blood streaming down his face. The 105 shell had caused the parapet to collapse on top of a soldier. Campana immediately assisted him and soon they could see the soldier’s helmet. Carefully removing the earth around the head and chest, the man was unconscious. Removing the rest of the earth, they placed the man on a tent-canvas and managed to revive him. No sooner than they had done so when another shell fell on the shelter were two men had taken refuge. One escaped with only a few scratches but the second had his legs broken. Moments later, one of Campana’s trusted stretcher-bearers had his arm torn off by a shell fragment.

I looked at the gasping body and bloody intestines and saw it was torn to shreds. He had no hope of recovering.

“Well what are you waiting for…my friends are as scared as the lieutenant to kill me off. Take pity on me…fucking kill me with a rifle shot…Why don’t you do something? Group of cows…bastards…you’re as much as a bastard as the officer.!”

I exchange a look with my men. They were quiet, but I saw in their eyes that they had grasped my thought and approved of it. With a heavy heart, I drew my revolver:

“Finally,” the wounded man groaned, then closed his eyes. I placed the revolver against his ear…Suddenly a hand grabbed my wrist, pushing the weapon away and causing it to drop, as a low voice murmured in my ear:

“Lieutenant, you don’t have the right to play God.” I turned and recognized the missionary.

“I don’t have the right to let this soldier suffer needlessly.”…The wounded man opened his eyes again:

“What are you worried about, you dirty crow!

“Try to put his intestines back in his body and bring a stretcher,” I tell Corporal Dubondieu. “Then transport him with one of your men to the first-aid post, avoiding as much as possible jolts and then come back quickly since I think I’m going to need you before too long. At least I have morphine on me!”

“You’ll kill us all, you damned lieutenant…damned priest…”

Losses for the regiment on 6 May include 9 killed and 14 wounded. The casualties recorded in the JMO include:

Killed: Sdts. Olivier, Chomet, Dubourreau, Lehousee, Ballion, Gueffieer, Morice, Bomiefous, Besnard.

Wounded: Sgt. Paradis, Proffit; Sdts. Mathieu, Petit (Jules), Goudy, Villemont, Chantal, Jeayot, Pelot, Prumier, Laroche, Peigné, Pronier, Arnaud.

7 May: The same entrenchment work continues, as does the German shelling which goes on unabated and claims more victims, including Campana and some of his most trusted me. By early in the morning of 7 May, another eight of his men were killed or wounded by shell fragments. There seemed to be a slackening of the shell fire, but to his right Campana could see the thick black smoke slowly rising up from the French positions, indicating that the Germans were attacking with flame-throwers again. A fusillade of small arms fire crackled above the fracas. This slowly died down only to be replaced by an intensifying in 105 shell fire.

Suddenly, two men ran towards Campana in an absolute panic and saying that another shell had landed squarely in the trench. He did his best to calm the men down, telling them they could stay by his side if it made them feel more at ease. The fusillade in the ravine to his right erupted again as German troops now moved toward the second French line. As he moved down the trench to check on his liaison agent, Campana suddenly felt as though his head and body had exploded. The next thing he was aware of was opening his eyes and being surrounded by his men. His eyelids felt heavy as he slowly regained his bearings. His greatcoat had been unbuttoned and was saturated with dark blood and mixed with the dirt.

“Am I wounded,” I asked weakly.They were the two men who had just previously come to stay with Campana. Macabrely, he took out his vest-pocket camera and took a photograph of them to record the close call he just had. In the end, Campana figured it had been a 210 shell that exploded behind them and buried him. He’d receive numerous contusions. He would find out later that the pressure from the crushing earth resulted in a tear in the lina alba by the bursting of the thorax muscles, called the rectus abdominus. Despite the severe pain, Campana knew he had escaped a horrible death that some of his comrades had not.

“I don’t think so, lieutenant,” my orderly said to me. “After we disinterred you, we looked you over and couldn’t find any wound. It must be their blood…”I turned and made out a horrifying sight. At my feet lay two bodies horribly mutilated. One was missing the head, with the backbone and shoulder blade rising up from the bloody flesh. The other was split open from shoulder to hips like quartered meat at the stall. The skull was split apart and the right eye torn out, and from the gaping eye socket, a thin trickle of dark blood flowed.

A fever overtook him and the pain from his injuries had become unbearable. Campana was ordered to report to the first-aid post by his captain. The walk proved exceedingly difficult in his injured state. Once he arrived, he was told he would be evacuated to Jouy-en-Argonne. Yet because of the large number of wounded, there weren’t enough vehicles to transport him there, so he was told he would have to walk the 3 km to the ambulance at Marre, along with any others who could do so. Along the shell-pocked road, he came upon trucks destroyed and flipped over by shell-fire and the bloated, putrefying bodies of horses that let off an awful stench.

Campana finally arrived at the ambulance at 0200 hrs on 8 May. Stretcher-bearers brought him in a large dirty room that was poorly lit. In it lay about fifty seriously wounded who’d been hurriedly bandaged and who waited impatiently to be evacuated. A chorus of cries of pain, wails of agony, and soft groans rose from the bloodied mass. No sooner than one of the wounded died, than nurses would come to move the body outside and replace the spot with another wounded. Campana thought he must be in Hell.

When a doctor finally came by to inspect him, he was told that the trucks would not go past Fromeréville and that he would have to walk the 6 km to Jouy from there. Accordingly, at 0400 hrs, Campana was transported to Fromeréville where he then began his long agonizing walk to Jouy. Each step he took felt like his chest was collapsing and a sharp cutting pain made it feel as though his intestines were being ripped out. The passing thought of killing himself occurred to him but he knew that would be a cowardly act.

Campana’s luck improved when a passing battery of artillery picked him up and let him ride atop one the caissons for the rest of the way to Jouy. While he was being treated there, Colonel Moisson himself came to pay Campana a visit. Moisson spent awhile kneeling down beside him, telling him that he would be evacuated to the Interior. The notion greatly upset Campana but the colonel reassured him that there was still plenty of fighting to do. He would return once he had fully recovered.

Yet this day would never come for Campana. After 6 months of recuperating in Lyon, he returned to the 151’s depot at Quimper, where he was declared unfit for service by the medical commission. Campana’s war was over.

Losses for the regiment on 7 May include 8 killed and 17 wounded. The casualties recorded in the JMO include:

Killed: Sgt. Ruellan; Cpl. Suire; Sdts. Lemaine, Bourdais, Cauqaun, Desyns, Gory, Verluys (one of the two killed beside Campana), Cry.

Wounded: Sdts. Badiere, Baudie, Beaudeau, Rouque, Perrigault, Pasco, Bonnel, Machu, Boyer, Eliot, Distribué, Corneau, Fenard, Jugliu, Quioc, Le Roy, Brechet.

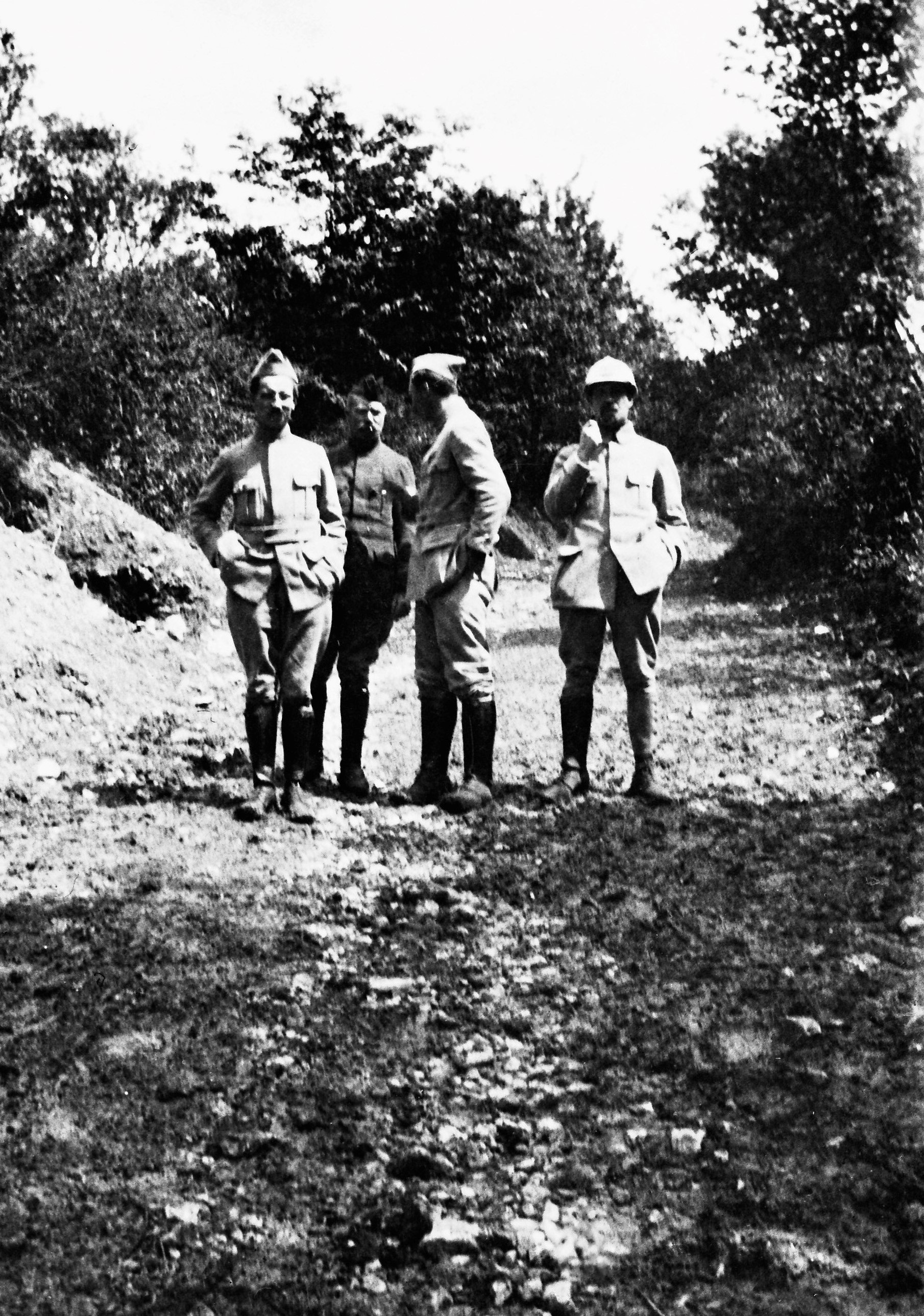

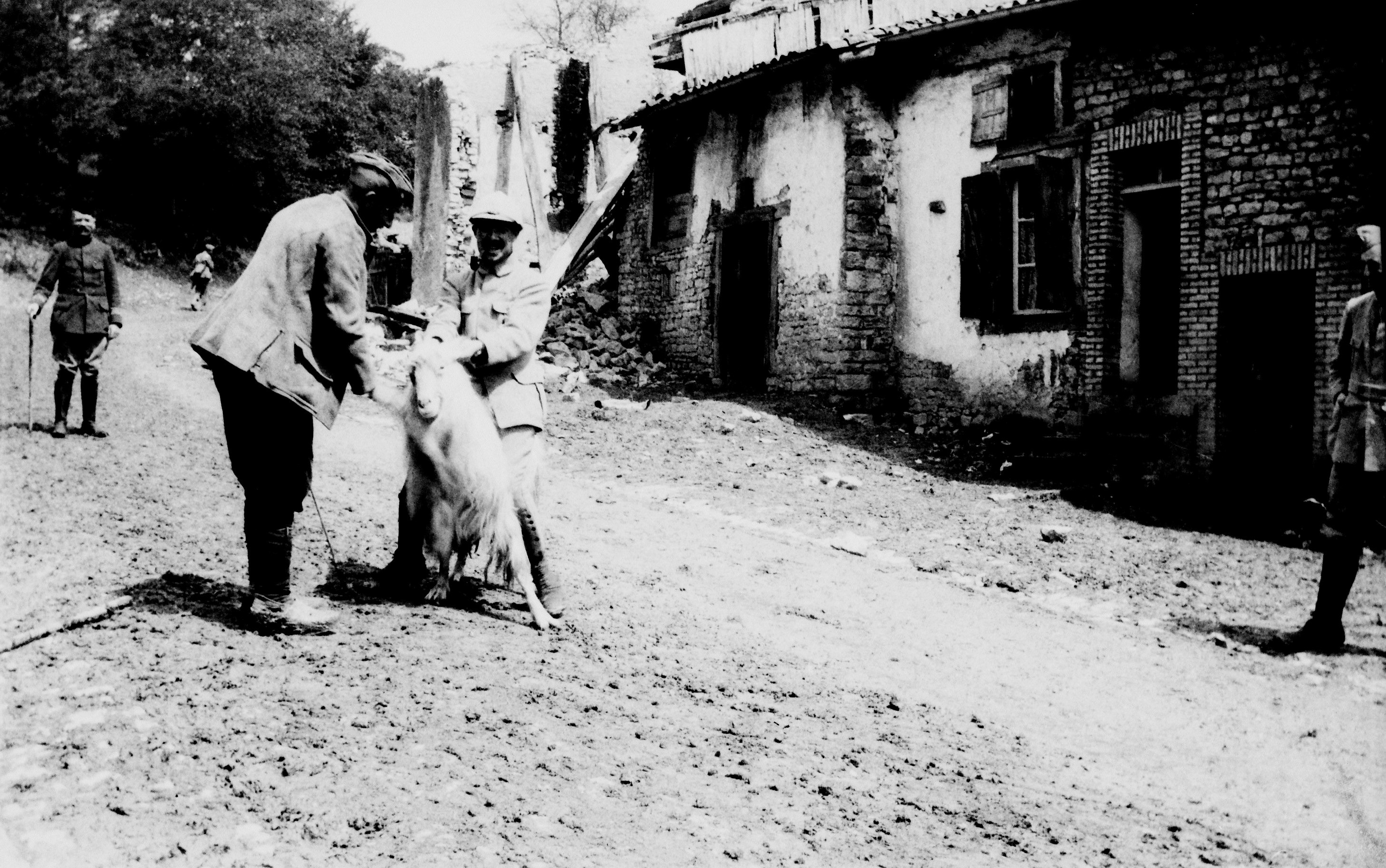

Jouy-en-Argonne - 17 May 1916. Photo taken by Capt. Tison, 151 RI.

8 May: The Germans continue to bombard the entire sector with all calibers of shells, particularly 77s. A small detachment of reinforcements arrives from consisting of Aspirant Boulanger (coming from the 151 depot) and one sergent, 1 caporal, and 13 men from the 27 RI. One of the men coming from the 27 RI was Sdt. Charles Bordinat. Originally mobilized in 1915 in the 58 Territorial Infantry, he was transferred to the 27 RI before eventually being passed to the 151 RI as a replacement. Upon arriving at the front he is sent up with the small group of other reinforcements to Jouy-en-Argonne where he was assigned to 6 Co., commanded by Capt. Olivier. At the moment, 2 Battalion was still up at the front lines at Mort Homme and would not rotate back to Jouy to rest until 18 May. In the intervening time, Bordinat and his companions would pass the days constructing chevaux de frise, waiting their turn to be thrown into the Furnace.

Losses for the regiment on 8 May include 1 killed and 3 wounded. The casualties recorded in the JMO include:

Killed: Sdt. Monniot.

Wounded: Sdts. Oddoéro, Dubuffet, Jouillaux.

9 May: The men work actively to improve the trenches and to set up barbed-wire entanglements across the regiment's front. The bombardment continues to rage on just as strongly. Detachments of reinforcements arrive from mixed units. These consist of: 1 sergent, 2 caporaux, 32 men from the 26 RI, 2 sergents, 2 caporaux, 30 men from the 134 RI, 1 sergent, 1 caporal, 19 men from the 160 RI, 1 sergent, 1 caporal, 15 men from the 79 RI, 1 caporal, 14 men from the 56 RI. Losses for the regiment on 9 May include 6 killed and 16 wounded.

10 May: The German artillery achieves a very accurate heavy caliber artillery fire and completely pulverises parts of first and second line trenches, making them almost untenable. Sous-Lieut. Giroux coming from 134 RI is assigned to 4 Co. Sous-Lieuts. Suisse and Thiebaud are promoted to permanently. Losses for the regiment on 10 May include 11 killed and 24 wounded.

11 May: During the night, Lieut-Colonel Moisson and his staff move up into the trenches to take command of the right sector of Mort Homme, replacing Lieut.-Colonel Matharel (162 RI). Lieut. Antoine is brevetted capitaine. Losses for the regiment on 11 May include 7 killed and 16 wounded.

Photos of 1 Bat. at rest in Jouy after completing its rotation - 16 May 1916. 1: Ritter, Huc, Lartigue, unknown, Julien. 2: Antoine, Oblet, Colin, Hugon. 3: Hugon, Oblet, Antoine. Photo taken by Capt. Tison, 151 RI.

Top: Lieut. Hugon and Sous-Lieut. Colin in Jouy-en-Argonne, with a possible billygoat regimental mascot - May 1916. Photos taken by Capt. Tison, 151 RI). Bottom: the same spot today from Google maps (location here).

12 May: The German bombardment of heavy caliber shells doubles in intensity, entirely obliterating the regiment's trenches in numerous places. Much activity is observed in the German boyaux, where troops can be seen moving from the front to the rear owing to the effect of French 75 shells on their boyaux. At night, the 3 Bat., which had been in reserve at Jouy-en-Argonne, moves up to relieve 2 Bat. in the first line. After the completion of this, the 3 Bat. is arrayed as follows from left to right: 9, 11, 12 Cos. in line with 10 Co. in support. Meanwhile, 2 Bat. rotates back to the second line to relieve 1 Bat., with the latter moving back to Jouy-en-Argonne in reserve. With 3 Battalion's return to the trenches, Jubert was now back on Mort Homme and provided a description of the scene:

Are beetles fond of corpses? In the first lines of Mort Homme, after the relief march, I spent all night surrounded by their buzzing constantly by their whirling. We took up the trenches at midnight in an inky black night that swallowed up the relief. Where were we? I couldn't say. The night held off any investigations. Even the flares only let out a weak sort of light, a halo drowned out in the distance. We only had our groping hands to supplement what we could not see and were ignorant of. In his haste, my predecessor had only bothered to indicate with a single word where there enemy was: "There!"Losses for the regiment on 12 May include 9 killed and 8 wounded.I tried questioning him in vain. I'd hardly thrown out my first question when he'd already made off into the night. He was gone, leaving me to me only devices to figure things out. My men in place in randomly chosen spots, passwords exchanged, recommendations made, I was left alone, isolated by a traverse from the last elements of my section. No niche to shelter in, no firing-step to sit on, tired of war, and with a worried mind from being in an unknown sector. I remained awake, standing up with my back resting against the parapet, blanket tied around my knees, feet sunken into the mud of Mort Homme.

Men called out to me in passing. They were lost and annoyed with me that I couldn't give them directions. Others in groups, brushed against or crashed into me. They carried heavy loads which brush past my face. The suffocating smell emitted as they pass and which for eight days impregnates my clothes indicates they're carrying corpses.

13 May: The day remains relatively calm. Between 1530 and 1630 hrs the Germans send over minens onto the 12 Co. Now in daylight, Jubert and his section was able to gain a better understanding of their new sub-sector.

At dawn, I stick my head above the parapet. Appearing in this sad gray of the morning and from a new angle is the vast battlefield that I've come to recognize. We are twenty meters below the main summit of Mort Homme. To the east of here, roughly two kilometers away, are the German positions, which lead to the Bois des Corbeaux. On our side and facing them up to the Bois des Caurettes are our gains from April 9th. And here, up to the point where we are at, the trench continues on. It's difficult night work, as we traced the trench out on April 11th and remained to this day in our handsJubert and his comrades were all in agreement: this was a bad spot to be posted in. The position was in the enemy's crosshairs and had already changed hands multiple times, sometimes in ferocious exchanges of hand-to-hand combat. Machine-gun fire and heavy shelling was a constant threat. The shelters were solid and the trenches were in constant need of repair. As the shelling got heavier, Jubert and his comrades amused themselves by lighting a match and watching with regularity as the flame was extinguished each time a heavy caliber shell burst nearby.What a look this battlefield has! For two months it did not stop. Is the trench we're in not the most disputed? Ten times, perhaps twenty times, it had changed hands. And in this vast field of death, gouged full of craters like a lunar landscape, everywhere before my eyes, the bodies of the enemy dead stick out of the ground.

A helmet shined thirty paces away from me, one belonging to an officer I thought. I jumped up to go retrieve it. Just at that moment, a machine-gun opened up. By the dozens, the bullets smacked down around me with the crack of a whip. I threw myself down, right onto a corpse. I rested against it at the bottom of a crater, a singular neighbor under hovering death. An elastic-like chest stuck out of the ground, upon which I stretched out and pressed my hand against. A sense of disgust overcame me at this jet-black mass from which a vile stench rose.

The obscene ugliness was revolting, more instinctually than from the actual disgust. Helmet under my arm, I lept up and making my way through the mud holes, build up my up my speed. I bent down under the bullets with uncertain footing, stumbling over the corpses. I could see the trench -- two more paces -- I'm safe.

Jubert had become increasingly introspective from the time he spent at Verdun. In great distinction to Campana's opinions, a cynicism bordering on fatalistm has soured Jubert's view of the war. He saw little redeeming qualities to draw from the war, no sense of personal glory (despite being a decorated officer himself). Reflecting on his role, he recorded:

The footsoldier serves no other purpose than to get himself crushed. He dies without glory, without élan in his heart, at the bottom of hole, and far from any witness. If he goes into the assault, he serves no other role than to place the signal flag to mark the furthest point of advance for the artillery fire. All his glory is reduced to recognizing and affirming the merits of the gunners. He honors a caste who, to him, has no skin in the game.Later, Jubert would lament more on the nature of the fighting, contrasting it to the romantic notions of combat he had held at the beginning of the war and what he would find on the battlefield.

After twenty months of fighting, where twenty times I should have died, I have not seen war as I had imagined it. No, none of those grand tragic tableaux, with sweeping strokes and vivid colors, where death would be a stroke, but these small painful scenes, in obscure corners, of small compass where one can not possible distinguish if the mud were flesh or the flesh were mud.Losses for the regiment on 13 May include 5 killed and 13 wounded.

14 May: An intense heavy bombardment opens up throughout the entire sector by all calibers of shells, with the greatest intensity at 12:30 am. The second line position in particular is heavily bombarded with a highly accurate fire. Lieut. Bouchaud coming from the Instruction Center of 3e Armée is assigned to 9 Co. Losses for the regiment on 14 May include 5 killed and 16 wounded.

15 May: The morning remains relatively calm but the violent bombardment begins again in the right sector in the afternoon with shells of all calibers. Losses for the regiment on 15 May include 8 killed and 22 wounded.

16 May: Intermittent bombardment throughout the day. At night, the 10 Co. goes to occupy the first line emplacements of the right-most company of the 162 RI (Tranchée des Poutres). A platoon of 6 Co. passes in support. Sous-Lieut. Hue returns after being previously evacuated and is assigned to 3 Co. and Sous-Lieut. Lemercier returns after being previously evacuated is assigned to 4 Co. Losses for the regiment on 16 May include 1 killed and 2 wounded.

17 May: The violent bombardments rages on but at certain times ceases completely only to resume again later. Chef d'Escadron (Cdt.) Lerval arrives from the Vernon remounting depot [cavalry] as the adjudant to the chef de corps. Lieut. Webancq arrives from the 151 depot and takes command of 8 Co. Losses for the regiment on 17 May include 2 killed, 6 wounded, and 2 missing.

18 May: The German bombardment continues unabated, an increasingly worrying sign for the men in the line. Jubert recounts what was happening in the first line positions, which 3 Battalion was currently occupying.

Each day we'd done reconnaissances. Since the first evening we'd arrived, at night we passed over the summit and got into an abandoned trench that had entirely filled with dead bodies. Going back two days later, Vandevoorde made out a living form five paces from him. He hesitated just as a gunshot burst in his face. Erkens went over next and saw that the enemy had cleared away the bodies. Lanckmans and I decided to try to take a look. No sooner had our silhouettes been made upon cresting the summit than two machine-guns opened up a crossfire on us. We took cover in a crater until down and glimpsed a working party. In Erkens' opinion we had discovered that the enemy had cleared away the old positions in order to make it into a departure trench.As Jubert mentions, on the night of 18-19 May, 1 Bat. leaves Jouy-en-Argonne where it was bivouacked and relieves 3 Bat. in the first line, with 3 Bat. rotating back to the second line positions. When the relief is complete, the 1 Bat. is arrayed in the following manner from left to right: 4, 3, 2, and 1 Cos. in line with a platoon of 10 Co. in support near the PC of the battalion commander. The other platoon of 10 Co. under the orders of Capitaine Destrais is placed in reserve of a battalion of the 162 RI on the left in the Netter shelters. The 11 and 12 Cos. are at the place d'armes at the disposition of Lieut-Colonel de Matharel commanding the sub-sector, while 9 Co. occupies the Ouvrage Laborderie in the second positions (located on height 259a few hundred meters to the south of the place d'armes) in liaison with Engineers Co. 6/3 ter. The 1 MG Co. is in the first line, supplemented by a section of 2 MG Co. The three other sections of 2 MG Co. are in the second position. Meanwhile, 2 Bat. is at rest at Jouy-en-Argonne, along with 3 MG Co. During the day, a particularly violent bombardment rages throughout the entire sector. Lieut. Caheu is transferred to 31 RI. Losses for the regiment on 18 May include 6 killed and 18 wounded.Under the continued bombardment, we’d only had a few losses. The reserve companies alone had suffered losses. Our advanced posts, our trenches were too close to the enemy. A shell twenty meters behind our lines, green flares by the dozens shooting up immediately from our lines, requesting the fire to be lengthened. This again added to our conviction that the enemy was getting ready to make a push. Barrage behind us before the attack on our front. They had sealed the approach routes with a curtain of steel. We were in the mousetrap. They felt so masterly that they’d neglected to strike us. They broke the branch to pick the fruit. We would be in their hands whenever they wished to come over.

We were secured our interior lines by doubling the watch our men. Our reconnaissance only served to prove to us that we still a day or two of respite. Our artillery now hit the works that constituted a threat. We felt the blow coming when our relief was announced. It was May 18th. This was the last time I would see several of my friends. We’d shook hands…I left with heavy heart. The danger held two-thirds of the regiment in a circle of steel. Closing in on them, it would be in less than two days’ time that my friends would be crushed.

Left: View of the southern slope of Mort Homme taken from the French first-line, 14 February 1917. La Place d'Armes appears in the right middle ground and the village of Chattancourt in the center background (source: Vallois Collection). Center and Right: Trenches on Mort Homme, including a German POW being escorted to the rear - 20 May 1916 (photos taken by Capt. Tison, 151 RI).

19 May: The relief is only just completed around 0400 hrs when the German artillery begins an disrupting fire on the regiment's positions. This fire is regulating by a number of German aircraft and lasts about two hours, in that the artillery fire seems to respond immediately and follows a slow, progressive fire with a density that increases up until noon. Starting around noon and lasting until 1900 hrs, the bombardment steadily increases in intensity, with the enemy fire consisting exclusively of heavy caliber shells striking with a remarkable precision. The Germans also send over a number of heavy minens on the first line, as well as numerous rifle grenades. Jubert provides a detailed description of his experience on this day.

When Jubert woke the next morning (now in the second line positions) he felt the ground trembling. He looked upon his sleeping comrades, struck by their undisturbed tranquility. At first he thought he might be dreaming himself but the sudden arrival and impact of shells around his shelter brought him back to reality. Three of his men had already been killed. New shocks shook the ground followed intermittently by a rain of earth. His men, panicked, pushed and shoved their way into the entrance to Jubert’s dugout. He orders them to take up their positions, shoving them back out into the trench. As soon as he emerges from his dugout he sees the approaching threat.

Coming from the enemy lines in an unbroken chain, several Taubes [German aircraft] stationed above our heads and firing machine-guns, transmit by agreed-to signals step-by-step instructions to correct the fire of their heavy caliber batteries. Arriving four at time, the shells completely flatten our line of shelters, targeting their fire at this moment to the extreme south where my section is found.Jubert and his fellow officers now wait in their trembling shelter for what the imminent attack to be launched, for the arrival of death itself. But a short time later, to their surprise, the Taubes had flown off and the shelling ceased. Jubert immediately ran with several of his men to check on the dead and wounded.With terrified faces, wide eyed and open mouthed, without saying a word, before this danger the company ebbs back to the center, not yet clear of the threat. And word arrives to let me know of a disaster: Pascal, Vandevoord missing. I clench my fists: they are the names of my sergeants!

There’s no stop to the reflexive flow. Besides, what purpose does it serve to hold these forty meters of ground where, closing in at four a time, the shells gather in. I slip back into my shelter. I smiled with pity: twenty centimeters of earth on a piece of corrugated iron, a ridiculous curtain to ward off death.

First, the survivors, lying flat at the bottom of the trench with round backs and faces buried in the ground, then the wounded with heads and hands covered in blood, eyes wide with dread, forgetting to moan, waiting for the lull that will allow them to suffer. I landslide, a white face sticking out of it, thrown back with closed eyes and mouth open to the sky. At the same height, outstretched and rigid, two white hands with open palms jut out of the earth. The first killed.Jubert and his men do what they can to disinter those partially buried but still alive. But the respite in the firing is short-lived and a short time later, the heavy shell starts back up with four heavy shells landing at a time. This time the firing has shifted to the north wing of the company’s positions, on the line of shelters spared in the morning. But the enemy had been observant during their morning barrages. To the localized fire in the reduced target zone, they added a progressive fire. New guns joined in this time and their shells traversed along the entire line behind the company, just where the surge of men had flowed back to escape the danger. Jubert was watching from the entrance of his shelter.Others follow in groups now in the churned up, filled in space, the positions my two sections occupied erased. To my eyes, there was no blood, no corpse entirely unearthed but enormous pyramid-shaped mounds of earth from which stuck out naked uninjured white and -- like bleached marble -- arms, faces, and hands.

Fifteen paces away, without any other protection over their heads except for a piece of corrugated iron thrown across the top of the trench, twelve or fifteen men are grouped standing one behind the other -- arms wrapped around the torsos with backs open -- one solid block against the danger. Men from the company, liaison agents of the colonel commanding the sector, those from three regiments elements of which, at this time, are under his command.The chain of Taubes had been broken. It was a small victory for the men on the ground as well, though this did not stop the shells from falling. Jubert doesn’t have the time to reflect further either way, as he is summoned by Lieut.-Colonel Martharel, the commander of the 162 RI who was in charge of the sector.A shell bursts in the middle of them. Under the powerful explosion which hides the sight from us for a second, all of this living flesh is in one blow made into a mass of death. Not a single shout. The earth collapsed in on top of them, I rush forward with wide eyes toward the horror. But suddenly behind me:

“Did you see that? Did you see that? He beat it, see, he beat it. The other one got away but he beat that one, he beat it. The Taube is heading back.

“Where? I don’t see anything.

“Over there, lieutenant, he’s coming down. Bravo, aces! Bravo!”

After the icy dread of death, the twists and turns of combat have reignited a flame in the men. Rid of their mutism, they shout and applaud. “Lucky pilots!” I yell at the top of my voice. Their victory or their fall both win the applause of those themselves die without any glory. In this war, there aren’t any more of those who have the life or the death that we dreamed of.

To reach him, I must climb over the recent victims, still pouring out blood and doing their last twitches. Two quartered bodies, with all their entrails torn out. Then a huge pile of earth, round, pyramid-shaped with a hole gouged out all around them. Sticking out of it by about forty centimeters and in a symmetrical fashion were legs, arms, hands, heads like the bloody cogs of some monstrous capstan.Once Jubert reaches the colonel, the two men acknowledge that Jubert’s company has suffered too many casualties to be able to mount a counter-attack when needed. Jubert’s company will have to be relieved. When he returns to his men to inform them of their imminent relief, he is shocked by the indifference to the news his men share.

“What good does it do to move, lieutenant?” someone says. “Here or somewhere else, we’re in the hands of bad luck.” All day this word followed me, tormented me, made me feverish. I hid it from my comrades. It’s already too much for oneself to be bothered. At night through the mist, where off in the distance brief flames followed one after another, I guide my men out, the head of a cortege of shadows. They were docile and mute, with blank, transfixed stares and lowered heads, like people who’ve not fulfilled their destiny. Like a ghostly sheepherder, I lead the troops of silent victims to their new stage of death.At the end of the day, the trenches are partly filled in, the boyaux no longer exist, and the repair of the trenches is made almost impossible by the bombardment, which continued on with the same force. Telephone communications were also gone, the wires being cut in numerous places. The second position suffered enormously under the bombardment. Losses for the regiment on 19 May include 11 killed, 27 wounded, and 2 missing.