First Hand Accounts of the 151e R.I

Lance-Corporal Henri Laporte

II. Verdun (cont.)

April 3

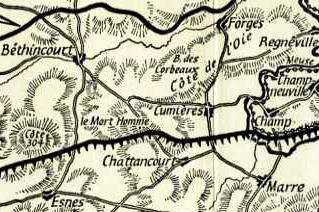

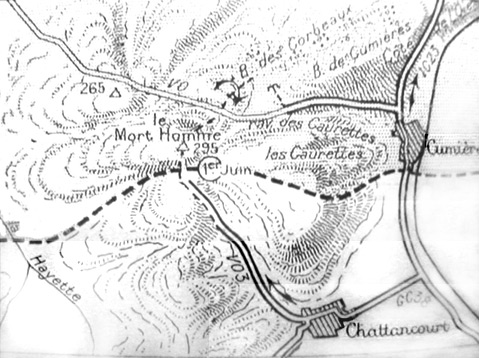

Twelve days after our arrival, we went back up again to the Verdun front, but this time we went to occupy the Mort-Homme sector of celebrated memory. After having crossed on foot through a large woods and several ruined villages, we entered the little town of what had been Chattencourt [Chattancourt]: the last one, the closest to the front. The shells fell continuously and many gaps were gouged out of our ranks before having reached our trenches.

April 4

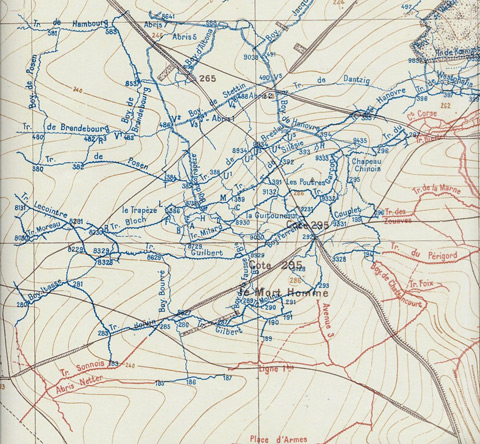

We take up position around 5:00 am on April 4 in the middle of a violent bombardment. Only the vestiges of trenches were left here, smashed night and day by bursting shells of every caliber. Rather, we were connected to each other by shell-holes (or really, excavations). Some shelters still existed. Our first day at Mort-Homme was bad. The German artillery, as well as the French artillery, gave us no respite. At night fall, the bombardment became less intense. I accompanied my captain in his inspection tour. Our company was set up on the flank of the hillside. The Meuse flowed by not too far from us (around 200 meters away). On the opposite side from the river was a small village: Esnes, at the foot of the famous Côte 304 ("Hill 304"). The artillery duel was raging over there now. Our first line of trenches was pretty well set up and hadn't suffered as much as the second line, which was 100 meters away. At 2:00 am, we went back to our shelter located between the first and second lines. The rest of the night passed without incident.

April 5

In the pre-dawn hours, the bombardment started back up stronger than ever and continued the whole day of April 5. The great battle of Verdun was building. Unfortunately, we have had rather considerable losses. Not a meter of ground was spared and it was a miracle that any human being could survive under this deluge of hell-fire. Everything was flashes, detonations, smoke. In the evening around midnight, taking advantage of a light calm, I left on a rations resupply, accompanied by eight poilus, volunteers. The "promenade" was certainly hazardous. We were leaving our positions when a rain of shrapnels [shells] hit us. One of the poilus in the party was thrown to the ground, killed instantly by a shrapnel ball in the middle of his head. We stopped for a moment and after relieving our poor comrade of his load of canteens, we set back off on our route right through the bursting shells.

Countless times, we threw ourselves down in order to avoid the huge fragments whistling their cry of death and raining down in all directions! After much excitement, we finally reached the small village of Chattencourt, which we crossed through without incident. "The small village"! Imagine piles of bricks and scorched beams with streets of water-filled shell-holes. It wasn't very easy to walk through on this black night, amidst all this chaos. About 2 km past the village entrance we found the rolling [field] kitchens. You can bet our cooking comrades welcomed us with open arms: "And over there? How's it going?" etc. Our provisioning finished, we rested a moment then started back fully loaded, the body wrapped up in canteens and stew-pots. While crossing through the village, we pass other fatigue parties. We weren't entirely alone, this route was the most practicable. After the spectacular chutes of mud came down, curses always ended in laughter. The main thing was to not lose the slightest portion of the precious rations.

We left Chattencourt in the direction of Mort-Homme around 2:00 am. The bombardment was going stronger than ever, with a gradual rising intensity as we advanced. We reentered Hell once again. We walked in zigzag in order to avoid (so we believed) the fire of the German batteries, which sometimes continued firing on the same point. We trudged on like this for more than an hour when all of a sudden, believing to be in our trenches, we heard shouts in a voice we knew all too well: we were at the edge of a German trench. In the pitch-black night, we had gotten lost. Needless to say, without weapons and with the precious rations, we all very quickly curled up in an enormous shell-hole. After no longer hearing anything suspect, we turned back on the direction in which we came with the great speed despite our load.

April 6

I've never been able to explain how, but an hour later we arrived safe and sound back in our good trenches this time (if we hadn't had the death of a comrade to mourn, we would have had a good laugh). It was around 5:00 am. We were given a good welcome. Our comrades were afraid that we had all been laid out in this desert of fire. A fatigue of this type made it back one out of two times. That's why we had to call on volunteers. Anyways, we hadn't been hit all that bad this time. I recounted our story to the captain, who couldn't help from laughing despite the circumstances. Don't we need to keep up morale?

The rations distributed, the fatigue men went back to their places in their sections. Separated from us by about 100 meters was a section that numbered at this time an effective of fifteen men. Our comrade who had been killed during the course of the fatigue had been in this section and as the fatigue volunteers from the other sections were going back to their emplacements, I took the stew-pots and canteens to give out the rations for this neighboring section myself. The 100 meters that separated me from them wasn't flat ground. Rather, it was an obstacle course: nothing but shell-holes. Fortunately, the bombardment was a little calmer. I had hardly gone 20 meters when I fell flat on my chest. I had collided with a big poilu whom I had knocked off his feet. He let out a curse which brought me to my senses.

My helmet in my hand, and before he had the time to get back on his feet, I landed a good blow on his head (his helmet, by good fortune, had rolled off onto the ground). It was a German who, without being fazed by the blow he had received, lifted his hands into the air, stammering out: "kamarad francais." The only weapon I had on me was my revolver, but it was hidden under my canteens and in my fall, I had tipped over half the stew-pots that contained the meat and vegetables. Making sure he didn't have any weapons (he was a young German of 18 or 19 years who was leaving his lines to surrender), I made him pass in front of me and brought him to the captain. He wasn't the first one who, for the last two days, had surrendered into our lines. This time I made the rations fatigue with a liaison agent with few delays. I was weary after this long walk over the smashed terrain!

I went to find my captain again. The interrogation of the prisoner wasn't over. The "Fritz" seemed content. He declared that they had suffered enormous losses. They had been sent as reinforcements, being previously on the Russian frontier. They had been told they were going to Paris! For them, Verdun was Paris!...But all they had managed to get up to now were shells of every caliber, which fell down without letup. The interrogation over, the prisoner was lead to the rear, accompanied by a liaison agent.

April 8

April 6, 7 and 8, the bombardment increased in intensity without cease, coming down as much on the first lines as on the reserve ones, and on both sides of either. We were all on high-alert in expectation of a large-scale attack. I have never witnessed such a deluge of fire. Insomuch, deafness had begun to overcome those who still remained upright. Around 9:00 pm, two [Germans] surrendered themselves into our lines. They spoke French well enough, saying they were Alsatians and that they wished to speak immediately to the sector commander. My captain and I accompanied them to the battalion leader's CP [Command Post], which was located 100 meters from us.

There, our two prisoners immediately declared that the Crown Prince's army was going to launch a large-scale attack at noon on April 9. These declarations concurred with other information already received and the amplitude of the bombardment couldn't deny it. We immediately received our orders from our colonel: take extra measures to those already made in anticipation of this attack. I made tours of our sector with my captain until midnight. A machine-gun, placed every ten meters, had its field of fire pre-sighted. Munitions were in abundance.

April 9

The morning of April 9, so as to mislead the enemy, our artillery, contrary to its practice, sent over only a few shells very far away from the interior of the German lines. Around 11:45 am, we were all at our combat posts, waiting for zero-hour. At noon exactly, a flare went up from the German trenches and immediately the first German assault wave went over top. They were all superb, strapping fellows. When this mass of men in tightly packed ranks had gone a dozen meters, the cross fire of our machine-guns literally mowed-down the first ranks. The second wave then took its turn and immediately suffered the same fate as the first. Those Germans, and there weren't many, who managed to pass through this storm of metal were taken down by rifles or grenades. Our artillery (guns of all calibers) came into action about five minutes after the German attack was launched.

What an inferno of fire! What an infernal noise! The unending German waves were all made of tightly packed ranks. They gradually grew larger. Heaps of bodies were already laid out in front of us. The muzzles of the machine-guns turned red. We fired without stop. From their part, our 75 canons created enormous devastation in the German trenches, just behind the assault waves. Our heavy artillery rained down on the German reserves without stop. The Germans continued to fall in front of our lines. It was a real slaughter.

One of our sections had lost all of its men except for one, Faglain*, who was able to save his machine-gun and continued to fire into the enemy waves. We took some losses, but nothing compared to the bloodshed across from us. Around 2:00 pm, the attack ceased. It had failed. But it had been the first bloody attack, especially for our enemies, since our arrival at Verdun. Thousands of their men were stacked up one on top of the other in front of our lines, the ones further away were countless. The Meuse, in counter-base, carried along streams of bodies. We (those of us who survived) looked like filthy chimney sweeps after this terrible massacre.

Soldat Faglain's actions are cited in the regimental historical, stating: "...the only one left of his machine-gun section, with an extraordinary calm, he set up his gun on the parapet and cooly mowed down the enemy columns which, after several attempts, flowed back in disorder, holding them off for two hours until a bullet came felling him across his gun."

Throughout the afternoon, we went about setting things back into state in the sector. We hurriedly brought up new guns with a strong supply of ammunition, for a new attack was anticipated, despite the losses inflicted. They didn't think much of their assault troops, sacrificing countless men. Our losses were less severe than theirs. On our right, the [8th] chasseurs had also held them off well.

April 10

Until midnight, the sector was almost calm. Then the bombardment started back up; a bombardment until then of unequaled strength. We were forced to make the most of the smallest shelter of fold of ground in order to stay alive, all the while holding the ground that we had been entrusted with. Not an inch of ground escaped the explosions. This time, we had considerable losses. It seemed the Germans wanted us to pay for their failure. This was their revenge. At 5:00 am, the bombardment was still just as intense. One heavy caliber shell, then two, then three, then by the hundreds. The 1st Section placed next to us, with thirty-five men, was completely crushed. I was sheltered with my captain and several poilus in a hovel [gourbi] constructed of interlaced logs and rails, which up till then had held up against the shots, despite some materials collapsing.

We stood guard in turns behind a small mound of earth to watch the front lines. Around 10:00 am, it became impossible to remain in this position. We were forced to stay at the entrance of the dugout. How had it resisted such a long time under a deluge of fire so formidable? Heavy shells exploded right on our shelter, shaking it more and more with each new detonation. As I said, the ceiling of our shelter was composed of railroad irons (at least five or six layers thick) interlaced with wood beams as big as tree trunks. It was an ex-German command post. The entrance of the shelter began caving in more and more. We continually scooped out the earth to keep form being buried alive! It's true that, now and then, we began to get discouraged. We were close to abandoning this convict labor. Our strength left us, we were completely dazed by this bombardment, which continued with the greatest intensity on both sides. The Hell of gunfire, explosions. The air that we breathed was simply smoke impregnated with the smell of gunpowder, which made us ill. We suffered from violent headaches.

Furthermore, there was an uninterrupted rumbling above us. Imagine hearing right beside you a dozen heavy freight trains barreling along with unbridled speed: this was the passing of French heavy shells on their way to reap death across from us. Around noon, still in the middle of the bombardment, a poilu from a regiment on our left in liaison with us fell in front of our shelter entrance, stricken by an awful wound in the back. The poor man howled in pain, called out for help, but it was impossible for us to give him the least bit of assistance due to the violence of the explosions. Alas, his suffering was prolonged...His dulled eyes reflected the approach of death. In the few words that he still muttered, alternating with vomitings of blood, he called out for his mother mamma. Though accustomed to seeing similar terrible fates, the heart ached. We couldn't speak a single word...

We were still evacuating and tossing out earth over our unfortunate comrade sprawled out, lifeless, very close by. Right at this moment, a heavy caliber shell exploded almost on the entrance of the shelter. We were buried; the comrades at the bottom of the shelter were already yelling at us to search for air. For those of us who were at the entrance, feeling the approach of death, our strength increased ten fold. Scraping out the earth with our fingernails, we soon started to dig a hole for air, although foul, to allow us to breathe again. It was a gas shell that had exploded. Working in shifts, we had to enlarge the hole and excavate the shelter entrance. The survival instinct had won! Sometime in the evening, the bombardment became less violent and with nightfall, we could finally leave our hole, which had really served as our tomb.

I accompanied my captain in our sector, which had been completely turned over. Only one machine-gun out of ten remained in a functioning state. The 2nd, 3rd and 4th Sections had their strength reduced in half. The trenches were reorganized as best as possible. With the inspection over, we made contact again with our neighbors to the left and right, placed on the same line as us. A liaison agent went to report the situation to the sector commander. The beginning of the night was calm. Around 1:00 am, the bombardment started back up with the same intensity, but about two hours later it quieted back down. Again, we've suffered losses; the two sections placed on our right no longer existed...

April 11

Day arrived, we had to entrench ourselves again, it was impossible to hold out exposed like this. And [the bombardment] lasts all day. For three days, we haven't been able to bring up any supplies. Hunger and thirst are particularly making themselves felt. Or strength begins to abandon us and there's no point in trying to organize any sort of fatigue party to the rear, to the kitchens.

Around April 12 or 13

Around 11:00 pm on the fourth day, April 13, a column of poilus, officer at the head, reaches us: it's come to relieve the 1st Machine-Gun Company of the 151st. What a relief for us, the few who had escaped! After having indicated our positions to the new arrivals, and after the captain had finished giving various instructions, we headed toward the village of Chattencourt. Six men remained in our poor company, six out of roughly thirty. Despite a heavy, sustained fire on our route, we arrived without a hitch at Chattencourt, which we crossed as quickly as possible. The presence of gas, lingering in the shell-holes and between the collapsed walls of the ruined village, gave us wings despite our great fatigue. We had already passed the dangerous zone, but up till then, we still hadn't encountered a single poilu from our regiment.

Here, unfortunately, my campaign journal stops. What I'm able to write now would only be remote memories, based on some notes taken randomly, without much detail. I'm going to try to recall the main events that I experienced until the end of the war.